2021 is the 70-year anniversary of the 1951 Edinburgh People’s Festival Ceilidh, the seminal event that heralded and generated the Scottish Folk Revival of the 1960s. Alan Lomax was on hand to record it in the Oddfellows Hall, and thus able to preserve a document of a legendary concert that alerted the astonished urban audience to the continuing vitality of Scotland’s rich heritage of traditional song. People in the rich folk culture of the Gaelic-speaking West, or speaking the Doric accent of the North East, still held and sang their vibrant old ballads and songs of work, but the Central Belt city folk thought the songs entombed in old books. Until the 1951 Ceilidh.

After it came a groundswell of enthusiasm for Scots song, house ceilidhs, concerts and campfires. The first of a wave of folk clubs began in 1960, with young people learning and singing the songs through lyric booklets and recordings. Dozens of artists—over the intervening decades to the present—have expressed the debt owed by Scotland to Ceilidh organizer Hamish Henderson and the original singers by sharing their own versions of songs performed at the event.

The People's Festival Ceilidh

In 1951 a grouping of left-wingers from the labour movement decided that a week-long People’s Festival must be organised as a necessary counterweight to the lofty highbrow events of the Edinburgh Festival. In the Oddfellows Hall were organised concerts and film shows, lectures on arts and the people, and theatrical performances.

On Friday night was a fund-raising ceilidh. The Gaelic word “ceilidh” originally meant a visit to a house, but it became an announcement of a more formal performance event. Hamish Henderson was put in charge of selecting the performers: two Gaelic singers, four North East singers, and a piper.

On Friday night was a fund-raising ceilidh. The Gaelic word “ceilidh” originally meant a visit to a house, but it became an announcement of a more formal performance event. Hamish Henderson was put in charge of selecting the performers: two Gaelic singers, four North East singers, and a piper.

Edinburgh-based Hamish Henderson (born in Perthshire in 1919; died 2002), was a collector of song and story; a discoverer of many key tradition-bearers; a poet, translator, songwriter, and towering figure in the Scottish Folk Song Revival. The Ceilidh recording shows his legendary manner of presenting song and music—warm and inclusive, enthusiastic yet wry, knowledgeable and delighted to share what he had found.

The remarkable piper chosen to frame the singing sequence of the Ceilidh was young John D. Burgess (1934–2005). Born in Aberdeen, he first learned to play the practice chanter at the age of four from his father John.

In 1950 John D. became, at the age of sixteen, the youngest-ever winner of the gold medals for piobaireachd at both the Argyllshire Gathering in Oban and the Northern Meeting in Inverness. Piper Seamus MacNeill described John as an infant prodigy who became a boy genius. According to Dougie Pincock, “the main things that set Burgess apart from his peers are his stunning technique, and the brisk speed that he takes a lot of the tunes at, even to this day. A successful competitor . . . but mainly known as a ‘showman’ piper, a great player, but also a great storyteller and character.” Despite the Irish tune names, the first two tunes appear as “pipe jigs” in Scottish collections, and the third title is in Scots fiddle master Niel Gow’s first collection of tunes.

Bothy Ballads

Bothies were very basic farm buildings where single ploughmen working with horses, and other less-skilled farm tasks, lived and messed together.

Many songs termed “bothy ballads” were made by North East Scotland farm workers that commented on their work and fellow workers, and often criticised their employers - c.f., “The Guise O Tough,” “The Barnyards O Delgaty.” (“Harrowing Time” and “The Hairst O Rettie” are less the work of a ploughman than of a local wordsmith maker or village bard.) The bothy ballad genre was later developed in the twentieth century into comic songs about farm life, made by local paid performers and songmakers like G.S. Morris and Willie Kemp. The song titles suggest humour: “The Sprotts O Burniebouzie”; “The Weddin O McGinnis Tae His Cross-eyed Pet.” Other songs gathered under the bothy ballad banner were not about farm life, but were sung of an evening in the bothy: “Skippin Barfit Through The Heather,” “Tramps and Hawkers,” “The Gallant Forty Twa.”

The language and pronunciation of some of the songs in the concert are deep in the Doric dialect of the North East. Most present-day people in the North East, let alone the rest of Scotland, would have difficulty in fully understanding “The Hairst O Rettie”— or “The Tinker’s Waddin,” which was made far in the south in Peebleshire. The makers glory in the richness of vocabulary. Robert Burns drew not on North East language, but the tongues of Ayrshire and Dumfriesshire, choosing which pronunciation depending on what rhyme he needed.

A wealthy farmer, he was said to have taken a kindly, paternalistic interest in the welfare of his fee’d men, and was a highly knowledgeable champion of songs of farm life and of fine versions of old ballads. In 1930 the American collector James Madison Carpenter recorded John on wax cylinders, and invited him to come and sing to students in Harvard, “but,” he demurred, “I wis pretty busy. I’d a lot o farmin to do.”

His first song is a bothy ballad, precise in date and location, commenting with a professional eye on the work conditions; naming and shaming the author’s fellow workers but, as usual, not including his own name. The farm of Guise is in the parish of Tough.

Aberdeenshire folk-singer, Iona Fyfe, has become one of Scotland’s finest young ballad singers, rooted deeply in the singing traditions of the North East of Scotland. Winner of Scots Singer of the Year at the MG ALBA Scots Trad Music Awards 2018, Iona has been described as “one of the best Scotland has to offer.” She is a bonny fechter in support of Scotland’s song traditions.

Bisset and Liberty Reapers (top and bottom)

The song celebrates how the mechanical reaper’s arrival in 1890 dramatically shortened hairst (harvest) time, and did away with the three-person teams of hand-scythe reaper, gatherer, and bander. It was written by blacksmith William Park of the huge farm of Rettie near the port of Banff. Willie Rae was the grieve (foreman) and, rather than have one of his horsemen drive the machine, he was working it himself.

The song reads like a TV advertisement for a new product, admired by a craftsman metalworker. Blacksmiths were themselves inventors and improvers of machinery. The 1890 Highland Show had a stand by Watson Brothers of Banff showing their “Victory back self-delivery reaper as designed by the late Mr. Murray, who was the first to bring out a back delivery reaper of the light pattern; and it must be gratifying to his successors to see other makers adopting the same principle.” At another stand Bisset of Blairgowrie showed their “Speedwell” machine. How pleased would the “jolly hairster lads” (some of whom would have been women!) be to have their casual income cut from 42 or 49 days to 32, even though they experienced less back-breaking pain?

As a fishwife living in the North East port of Buckie, Jessie Murray would have trudged from door to door, “a little lady” dressed all in black, wearing a black shawl, and with a basket of fish or shellfish on her back. She was a fisherman’s widow, aged at least 70 in 1951. In the 1950s she was cared for in a home for elderly people. One day a visitor called, and a staff member said anxiously, “We worry that she’s going from it. She thinks she is going to be on the radio tonight.” The visitor replied, “She is, on an Alan Lomax programme!”

“I always remember Jessie Murray, and she came forward and gave a little curtsey to the audience. and she sang ‘Skippin Barfit Through the Heather,’ and of course these were songs you had never heard, and clearly the whole audience had never heard either.” —Janie Buchan, Radio Scotland, 1994.

Skippin Barfit Through The Heather

Gordeanna’s CD cover shows her with papier-mâché figures made by Jan Miller of core influential traditional Scottish singers: Jimmy MacBeath; white-haired Border shepherd Willie Scott; and travellers Davie Stewart and Jeannie Robertson. All but Scott were recorded in detail by Lomax.

At school in Rutherglen beside Glasgow, Gordeanna was taught English and given a lifelong love of Scots song by Norman Buchan (who had helped organise and was inspired by the 1951 Ceilidh), and was reportedly “stunned’ by this song sung by Jessie Murray. Though the lyric is in a man’s voice, the song was much more popular with and often recorded from women singers.

At school in Rutherglen beside Glasgow, Gordeanna was taught English and given a lifelong love of Scots song by Norman Buchan (who had helped organise and was inspired by the 1951 Ceilidh), and was reportedly “stunned’ by this song sung by Jessie Murray. Though the lyric is in a man’s voice, the song was much more popular with and often recorded from women singers.

The modern versions in this Exhibit of songs first sung in the Ceilidh show how later performers have drawn on and combined Scottish, American and Irish traditional instrumental techniques to accompany the songs.

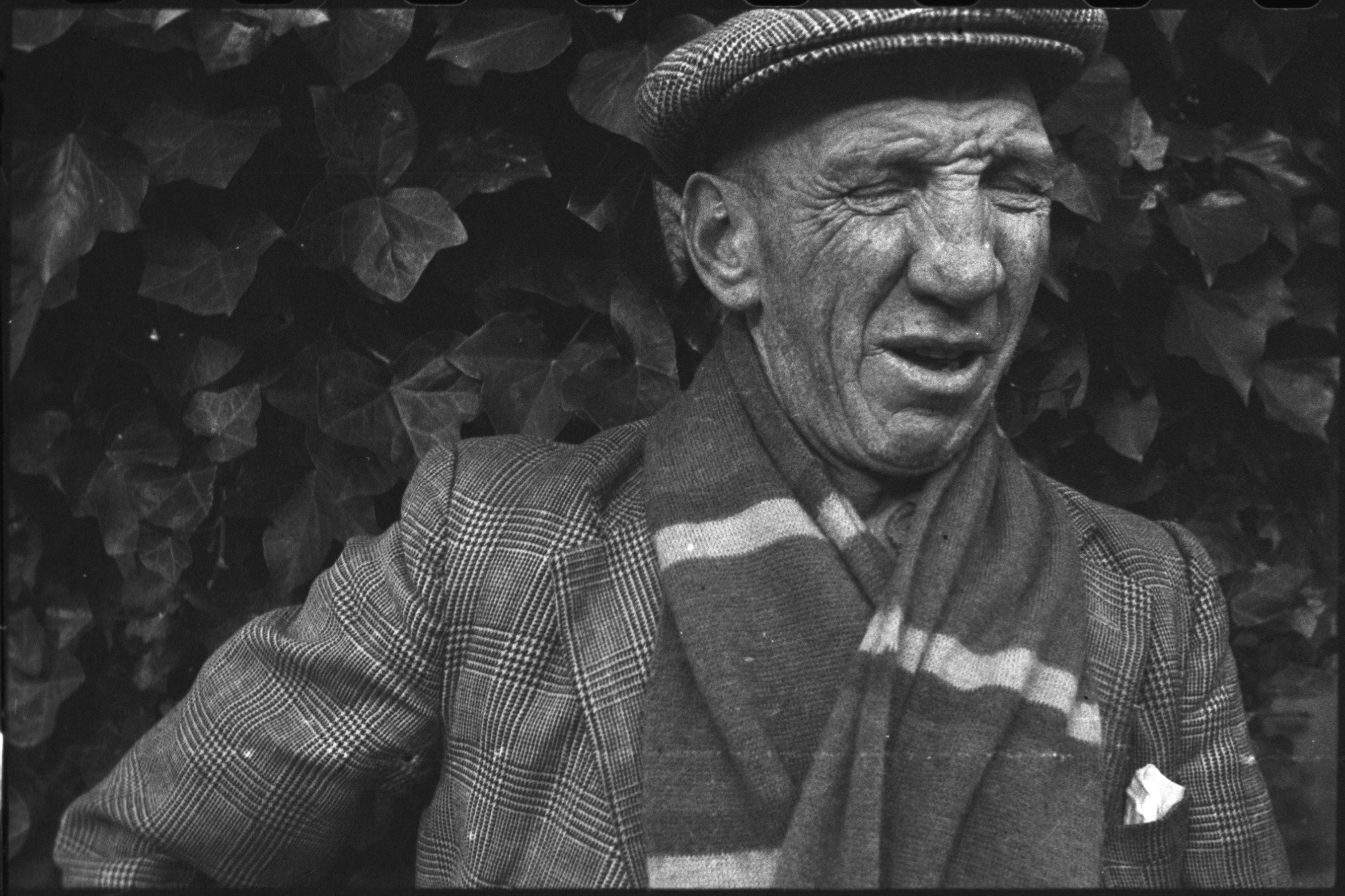

Jimmy was not a tinker, but of settled folk. He was born in the Buchan fishing village of Portsoy in 1895 and died in 1972. For most of his life Jimmy footslogged the roads of Scotland and beyond, earning pennies from singing the streets, and shillings from casual labour, living in “model” public lodging houses. At the end of the Ceilidh he informed the audience that this was his “swan-song” the culmination and the conclusion of his singing career: for reasons of ill-health and age he would never be able to sing at a similar function again.

Jimmy was not a tinker, but of settled folk. He was born in the Buchan fishing village of Portsoy in 1895 and died in 1972. For most of his life Jimmy footslogged the roads of Scotland and beyond, earning pennies from singing the streets, and shillings from casual labour, living in “model” public lodging houses. At the end of the Ceilidh he informed the audience that this was his “swan-song” the culmination and the conclusion of his singing career: for reasons of ill-health and age he would never be able to sing at a similar function again.

But in the 1960s Jimmy began to be recorded commercially and to sing in folk clubs and festivals. Alan Lomax described him as “a quick-footed, sporty little character, with the gravel voice and the urbane assurance that would make him right at home on Skid Row anywhere in the world.”

Tramps and Hawkers

This is one of the most popular songs of young Revival singers, said to have been first made by Besom Jimmy, a much-travelled Angus-born hawker of the 19th Century who decorated his coat with feathers. Francy [left] has topped and tailed the lyric with dreaming verses written by Alan Reid of the Battlefield Band. Francy has a Scottish heritage, an English early upbringing and strong Irish roots, and is a core mover and shaker in the singing circles of Ireland. Scots singer and musician Steve Byrne supports Francy on this track. Steve is another prime organiser, a founder and continuing member of the innovative group Malinky, and an influential activist in the Scottish traditional music scene.

This is one of the most popular songs of young Revival singers, said to have been first made by Besom Jimmy, a much-travelled Angus-born hawker of the 19th Century who decorated his coat with feathers. Francy [left] has topped and tailed the lyric with dreaming verses written by Alan Reid of the Battlefield Band. Francy has a Scottish heritage, an English early upbringing and strong Irish roots, and is a core mover and shaker in the singing circles of Ireland. Scots singer and musician Steve Byrne supports Francy on this track. Steve is another prime organiser, a founder and continuing member of the innovative group Malinky, and an influential activist in the Scottish traditional music scene.

The 42nd Highland Regiment, also known as the Black Watch from the dark government tartan they wore, was formed in 1739 to keep dissident Highland clans in order. This lighthearted theatrical song, with its listing of Scots regiments, shows Jimmy’s warm and winning way with songs other than those of farm life.

The song refers to the blue bonnet with white cockade worn by Jacobite supporters of the deposed Stuart king, James VII of Scotland and II of England, and of his heir, Charles Edward Stuart, known as Bonny Prince Charlie. “Blue Bonnets” is a metaphor for the Scots marching men who went “over the border” into England seeking a fight.

Sir Walter Scott’s landmark work, Minstrelsy Of The Scottish Border, collected together many ballads of cross-border strife and warlike action. Borderers raided on both sides of the hilly Debatable Lands.

Scott’s own lyric names here where some of the prominent Borderers had their high towers. Is the Queen he refers to Scotland’s tragic Mary Queen of Scots?

About the Gaelic Language and Gaelic Song

Gaelic is the old language of much of Scotland, but now those who speak it are mainly from the Hebridean Islands or the north west mainland, the Gaeltacht. The oldest Gaelic songs are about the legendary heroes the Fianna, and go back over a thousand years. For hundreds of years the clan chiefs supported their own poets and musicians, their bards, harpers and pipers. In the last three hundred years, famous or locally celebrated Gaelic bards have set their words to known tunes to create their fine songs. In the Ceilidh three songs of Jacobite times were sung, two of welcome and one lamenting.

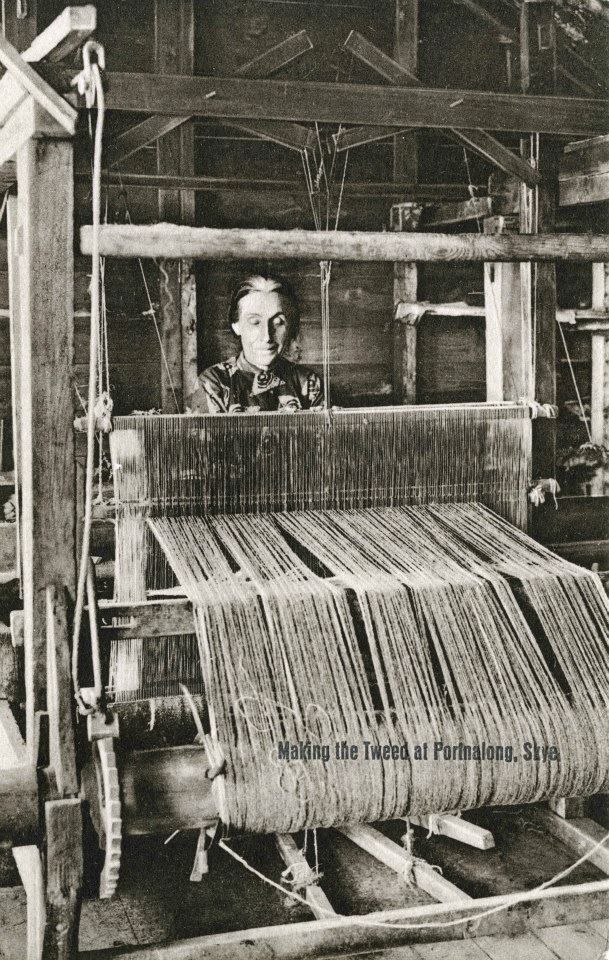

Other Gaelic songs were used to support and lighten work tasks, particularly the famous waulking songs. These were sung to lighten the task of groups of women who had gathered to help shrink newly woven tweed by beating the wet cloth rhythmically on a table. Alan Lomax went collecting widely across the Gaeltacht, and became very enthusiastic about the more than 250 songs he recorded in a few days, later describing what he found as “the flower of Western Europe.”

In 1953 Lomax was the subject of a six-part BBC TV series called “Song Hunter: Alan Lomax,” directed by a youthful David Attenborough. Without clearing the action, Lomax invited a group of island women to demonstrate waulking. Attenborough ruefully commented that their airfares had used up half the budget for the whole series.

In a 1951 BBC radio programme Lomax said,

“The tweed, enough for a suit, has been hand-woven, and is now to be shrunk. Six women sit at a long table, the long roll of cloth wet with shrinking solution, is being passed from hand to hand round the table, each woman grasping it, squeezing it, rubbing it against the table and passing it to their neighbour on the right. Grasp, rub, move, a swinging, relaxed triple rhythm, all six bodies coordinated so that the cloth never ceases a regular flow from hand to hand. Every once in a while they stop to measure and chat, then the song goes on.’

Oran Eile Don Phrionnsa (Another Song To The Prince)

Calum Johnston (1891–1973) was born in the Outer Hebridean island of Barra, worked as a draughtsman in Edinburgh, and retired to Barra. He died suddenly while playing his pipes for the funeral of novelist Sir Compton Mackenzie in violent weather. Calum and his sister Annie made a large number of invaluable recordings for the School of Scottish Studies. They came from a family of eight, raised on a croft near Castlebay on the Isle of Barra. Annie became a schoolteacher at Castlebay School, and was very helpful to Marjory Kennedy-Fraser’s song collecting there. Calum became a prominent Gael in Edinburgh and was secretary and treasurer of the Highland Pipers’ Society. His song expresses delight in 1745 at news of the impending arrival of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, “Bonny Prince Charlie.” It was composed by Alexander MacDonald (c.1700–1770), who was a first cousin of the famous Flora MacDonald. Alexander was the son of a clergyman in Ardnamurchan.

Calum Johnston (1891–1973) was born in the Outer Hebridean island of Barra, worked as a draughtsman in Edinburgh, and retired to Barra. He died suddenly while playing his pipes for the funeral of novelist Sir Compton Mackenzie in violent weather. Calum and his sister Annie made a large number of invaluable recordings for the School of Scottish Studies. They came from a family of eight, raised on a croft near Castlebay on the Isle of Barra. Annie became a schoolteacher at Castlebay School, and was very helpful to Marjory Kennedy-Fraser’s song collecting there. Calum became a prominent Gael in Edinburgh and was secretary and treasurer of the Highland Pipers’ Society. His song expresses delight in 1745 at news of the impending arrival of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, “Bonny Prince Charlie.” It was composed by Alexander MacDonald (c.1700–1770), who was a first cousin of the famous Flora MacDonald. Alexander was the son of a clergyman in Ardnamurchan.

Oran Eile Don Phrionnsa (Another Song To The Prince)

From Tullywiggan, Co. Tyrone, Daibhidh originally heard the song sung by Karen Matheson, then researched versions on the Tobar an Dualchais (Kist O Riches) website. In 2018 Daibhidh became the senior traditional singing champion for Tyrone and Ulster. He sings in the Ulster and Scots dialects, and Irish and Scots Gaelic.

Co Sheinneas An Fhideag Airgid? (Who Will Play the Silver Whistle?)

[NB: The beginning of this song was lost when Lomax had to change over his recording tapes.]

Flora MacNeil was born on the island of Barra. When she moved to work in Edinburgh in 1947 “she was already a most accomplished traditional singer, with a repertoire more varied and more extensive than anyone else of her age.” She became one of the leading figures in the post-war revival of traditional Gaelic song. On a 1951 recording in Edinburgh she leaves the room after singing, then Lomax is heard to ask, “Gee, who’s the dish?”

Co Sheinneas An Fhideag Airgid? (Who Will Play The Silver Whistle?)

Dr. Anne Lorne Gillies’ family had a croft “tucked away under the hills on the southern outskirts” of Oban. She won the Mod Gold Medal for Gaelic singing in 1962. She writes: “This anonymous work-song borrows the conventional praise-poem image of a much earlier era to give us an unmistakable Gaelic flavour.” (This and Gillles’ other comments on songs are from her 560 page book, Songs Of Gaelic Scotland, Birlinn 2005, winner of the 2006 Ratcliff Prize.)

On the Water

There are many songs of travel or work on the water in the Gaelic and Scots traditions. Here are singers Barbara Dickson and Archie Fisher singing a Scots Jacobite song that had been worked over by Robert Burns, “Ower The Water Tae Charlie.” They and Billy Connolly talk about the early days of the Scottish Folk Revival.

Banjo-playing Connolly began as a Glasgow-based performer of US Old Timey numbers like Cripple Creek, his song introductions lengthened till he became a comedian with a fearless freewheeling observational style, then an actor. Barbara Dickson went on to have Top Twenty hits, then became a dramatic actress before returning to her folk roots world, whereas Archie Fisher continued to make many fine LPs of traditional and original songs, to broadcast for many years as presenter of BBC Radio Scotland’ Travelling Folk, and to collaborate with Irish and Canadian singers.

On the Land

Most of the songs and tunes in the Ceilidh, and the others in Scotland’s great bundle of songs and tunes, are very specific about the location of the piece and its home place.

Fyvie, Portnockie, Mormond Hill, Strichen, Aberdeen, Burreldale, Glasgow Green, Edinburgh, Banff, Vaternish, Bannockburn, Tough, Delgaty for a start. Many fiddle tunes are named for patrons and their home places.

Dougie Pincock writes: This is the air of a fairly modern Gaelic song, composed by John Ferguson from Vaternish. Oddly, the tune title in translation means “Welcome to Rhu Vaternish,” while the English name of the tune is “Leaving Rhu Vaternish.” “Failte” is “Welcome”; “Leaving” would be “Fagail.” Rhu Vaternish is Vaternish Point, the northernmost part of the peninsula of Vaternish, in the North East of the Inner Hebridean island of Skye.

Pipers distinguish between Céol Mór (Great Music) and Pibroch, the classical music of the Highland pipes, and Céol Beag (Little Music). The marches, reels, jigs and song tunes played at the Ceilidh are all Céol Beag. Céol Mór includes salutes (tunes addressed to someone of importance), gatherings (tunes used to gather members of a clan), laments (tunes expressing sadness at someone’s death) and tunes associated with historical events. Pibroch is slow and sombre, with a theme which is varied throughout the piece, gradually becoming more complex and rhythmic, then returning to the basic theme at the end.

The Bonny Lass O Fyvie & The Silver Spear

John Strachan had voice problems all through the Ceilidh. Luckily his voice was in much better fettle during the recording session Hamish Henderson and Alan Lomax held with him at his home in Crichie, a month earlier in July 1951. There he gives seven spirited verses of this martial Aberdeenshire song of death for love, hardly known in 1951, but since then very popular in Scotland in “sing-along-a-tartan” style. Bob Dylan recorded an American version, “Pretty Peggy-O,”’ which he had learned from the singing of George and Gerry Armstrong.

For over twenty years the Malinky group have continued “their distinctive mission as contemporary champions of traditional Scots song.” The lead singer is Karine Polwart, who has since become one of Scotland’s finest songwriters in traditional mode.

Mormond Braes

This song was well known in a settled, rather bowdlerized text taught in Scottish schools, as we can hear from the audience joining in the chorus. Appreciative laughter greets John’s more earthy verses and vigorous singing style. Collector Gavin Greig called the rich tune “a perfect one-strain melody.” John Strachan farmed at Fyvie, and the market town of Strichen is eighteen miles away, with Mormond Hill just North East of it.

Aileen comes from a Perthshire family where music was a core part of life, although she was the first to sing upon a stage—working as a teacher, she began performing unaccompanied in folk clubs and festivals. A concert review said of her, “There was nothing to beat the full-blooded, attacking style of Aileen Carr. At her powerful wha-daur-meddle best.”

I’m A Young Bonny Lassie

Italian group Morrigan’s Wake are based in Ravenna near Rimini. They say “Morrigan's Wake is a musical group that offers a traditional repertoire from the Celtic area of Northern Europe, in particular Scotland and Ireland.” Their musicianship is outstanding, as is their obvious love of and respect for the music they choose to perform. When invited to contribute this track they replied that “It is a Great Honour for US.”

Singer Massimo Pirini found Blanche Wood’s recording on “an old album called Heather and Glen.”. (Tradition Records, 1961.) This album was Alan Lomax’s second gleaned assembly of his Scottish recordings. Here Massimo does not attempt Scots pronunciation of the lyrics, which blots out some of the rhymes. A tasty version for all that.

“Brown-haired and bonny Blanche Wood. Hers was the clear, bell-like voice one hears so often in the North.” —Alan Lomax on BBC Radio, 1957.

Blanche was born a K-nocker—that is, a resident of the small fishing village of Portknockie, five miles east of the port of Buckie. In 1951 she was 18, and in the Ceilidh she sang songs her aunt, Jessie Murray, had taught her. Blanche’s father was a fisherman. He named a new boat for her, The Girl Blanche, launched by Blanche herself at age 15. Blanche married Robert Allen, who sawed the keels for fishing boats; but by 1961 the boatyards had shut, and they moved to Edinburgh where they still live. Blanche and her sister formed a singing act that toured working men’s clubs in Scotland and England, singing “more modern songs.”

This beguiling song is “absent from the older collections.” The tune is better known as the Irish “Brian O’Lynn.”

The audience has by now begun to cheer what they are hearing, and applause swamps the recording level.

A small morality lesson on the evils of the demon drink, reminding us of the strength and manipulative vehemence of the nineteenth-century temperance movement. The transcript of this song in the School of Scottish Studies archives is annotated, “This hodden-grey tear-jerker is a find - can’t trace it in any of the earlier collections.” (It is in fact in Ord’s Bothy Ballads). Another such song was addressed to the publican: “Don’t sell daddy any more whisky.”

Johnny My Man

Four talented and individually prominent singers and musicians from both sides of the Border, ‘Innovative arrangements, yet never losing the essence of their roots’.

John’s recording was reduced to two fragments, as Lomax had to change tapes again. This recording comes from The Rounder Portraits album ‘John Strachan, Songs From Aberdeenshire’.

The tune is one that in the North East is most associated with the favourite song Drumdelgie, which details many of the tasks of the horseman’s work. ‘Harrowing Time’ concentrates on one aspect, the harrowing – dragging a heavy-toothed frame over ploughed land to break up clods and even the ground. John omits two verses in which the ‘hard farmer’ gives the men no rest, but he keeps in the request for a pay rise.

About Ballads

What is a ballad? A narrative song in short stanzas. Scotland is rich in them. Some of the songs of the Ceilidh are the “Big Ballads”: “Barbara Allen,” “Lord Thomas and Fair Ellen,” “Johnny O Braidislie.” These were severely studied and given standard reference numbers by American scholar Francis J. Child.

Some are smaller: “The Bonny Lass O Fyvie,” “Jamie Raeburn,” “Erin Go Bragh,” “MacPherson’s Rant,” “Scots Wha Hae.” Some are very local— “Mormond Braes,” Portnockie Road,” “The John Maclean March”—and others are the songs of farm and bothy life discussed earlier.

In Scottish Ballads Emily Lyle comments, “Reactions to this exceedingly widespread ballad have been varied; while some have been moved to tears, others have been impatient with its hero.” She instances the comment of Bertrand Bronson that the song had shown “a stronger will-to-live than its spineless lover.” Some versions justify the apparent heartlessness of Barbara by explaining her swain had spoken slightingly of her in the alehouse.

In Jean Ritchie’s sweet-voiced 1949 recording for Lomax she shares twelve verses. When Scot Allan Ramsay edited his 1763 collection The Tea-Time Miscellany, he gave nine verses. Richard Bronson amassed 200 tune versions in his The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads.

Johnnie Brod

Academic Dr. Katherine Campbell has recorded, written and edited or co-edited several important works about Scotland’s song and ballad tradition, including Volume 8 of the Greig-Duncan Collection; The Fiddle In Scottish Culture; Songs From North-East Scotland; the Walter Scott Minstrelsy project and the website www.scotssangsfurschools.com. On this CD she sings ballads from the 1955 rediscovery of “a lost manuscript of a unique traditional ballad repertoire of two sisters.” Katherine Campbell sings a version of the ballad written down with the tune by Amelia Harris. She and her sister Jane learned them from their mother Grace when living in the village of Fearn in Angus. Grace Harris had learned many of her ballads in Tibbermore, Perthshire, from an old family nurse, Jannie Scott, who had been with the family since 1745.

Academic Dr. Katherine Campbell has recorded, written and edited or co-edited several important works about Scotland’s song and ballad tradition, including Volume 8 of the Greig-Duncan Collection; The Fiddle In Scottish Culture; Songs From North-East Scotland; the Walter Scott Minstrelsy project and the website www.scotssangsfurschools.com. On this CD she sings ballads from the 1955 rediscovery of “a lost manuscript of a unique traditional ballad repertoire of two sisters.” Katherine Campbell sings a version of the ballad written down with the tune by Amelia Harris. She and her sister Jane learned them from their mother Grace when living in the village of Fearn in Angus. Grace Harris had learned many of her ballads in Tibbermore, Perthshire, from an old family nurse, Jannie Scott, who had been with the family since 1745.

Katherine writes: “This superb ballad (Johnie Cock: Child 114, Greig-Duncan 250) has remained strong in the living tradition in Scotland down to the present day. The Harris version was learned around 1790 and provides the earliest copy of a tune.”

John seems unprepared to sing this but makes a fine work of the exciting saga of Johnnie, the noble deer poacher, who fights off the King’s Foresters (gamekeepers). In some versions they kill him; in others he escapes. Here John omits the elegiac final verse that he sang a month earlier for Henderson and Lomax, in which Johnnie’s bow is broken, his dogs slain, and “His body lies in Monymusk, and his huntin days are deen.”

This is a most favourite ballad in Scotland. The Greig-Duncan Folk Song Collection shares 22 versions sung to them in the North East in the first quarter of the twentieth century. The longest has 26 verses.

Sweet Willie and Fair Annie a.k.a Lord Thomas a.k.a The Brown Girl a.k.a The Nut-brown Maid

The singer here is Steve Byrne, who works tirelessly on several fronts in the cause of Scotland’s traditional song—performing, promoting, organising and supporting. His rich text draws on versions collected by Gavin Grieg and Rev. James Duncan.

This is another ballad of love’s confusions that is sung throughout the English-speaking world. Lord Thomas’s parents have urged him to marry for money. The ballad story continues with the brown bride taking offence at Lord Thomas’s protestation of love for Ellen and stabbing her to death. Lord Thomas kills his bride, then himself.

Lord Thomas he was standing by

His sword ground keen and small

With one swipe he cut off his bride’s head

and kicked it against the wall.

All three bodies are laid in one grave, and our “hero” continues to show his contempt for his new bride.

Bury Fair Ellender in my arms, the Brown Girl at my feet.

Announcement of interval, tea and cakes

Hamish, a noted toper, is amused that tea and cake are on offer at the back. He himself would have popped just across the road for a dram in his favourite howff, the Foresthill Bar, now called Sandy Bell’s (itself a central site for folk revivalists’ music-making).

Announcement of continuation of Ceilidh

John Strachan complained about the theatre lights that stopped him seeing his audience. These were rigged for plays performed on the other evenings of the Festival,”‘In Time O Strife” by Glasgow Unity Theatre, and “Johnny Noble” and “Uranium 235” by Theatre Workshop. The latter two pieces were written by Ewan MacColl and directed by Joan Littlewood.

The Ceilidh had been organised specifically to help meet the costs of bringing Theatre Workshop to the Festival. Theatre Workshop was noted for its innovative use of lighting effects and “soundscapes.” One of the Ceilidh singers had a particularly strong effect on Ewan MacColl, then thought of as a playwright and actor who also sang old songs. Hamish Henderson wrote, “The sight of Ewan’s face, when he first received the full impact of Jimmy’s personality and performance, remains vividly in my memory.”

Dougie Pincock writes: “These two jigs are what most people would think of as typical of Burgess’s playing. ‘Donald MacLean’ was probably composed by Peter Macleod, and ‘The Irish Washerwoman’ is a hallmark of Burgess’s playing—he isn’t particularly known as a composer, but he has done some stunning arrangements of traditional standards, notably ‘The Mason’s Apron.’”

“The Irish Washerwoman” is more popular outside Ireland than with Irish musicians. “It has been proposed by some writers to have been an English country dance tune that was published in the seventeenth century and probably known in the late sixteenth century.” —Kuntz, The Fiddler’s Companion. The Companion tells us of “The Snouts and Ears Of America,” an apparent “derivative” version of the Irish Washerwoman tune in 4/4 time, with an “incomprehensible” title, played by Mrs. Sarah Armstrong, (near) Derry, Pennsylvania, Nov. 5, 1943.

Alan Lomax was tipped off about Margaret Barry, and found her busking in Dundalk, Eire in 1951. This track was recorded in 1953 in London, where she would become a fixture at Irish trad sessions in Camden Town pubs. Photographs show her playing an English-made 5 string Windsor Pioneer banjo.

“Erin go bragh” means “Ireland for ever.” Gavin Greig says this song was “an exceedingly popular ditty . . . with the general crowd” in the North East, who had a healthy admiration “for pluck and independence.” The story reminds us that Scottish support for political rights in Ireland is no new thing. The hero is of a clan identified with Protestant support of the Crown, yet has the look, manner, and actions of a Fenian rebel against English rule, and his blackthorn stick identifies him with Ireland.

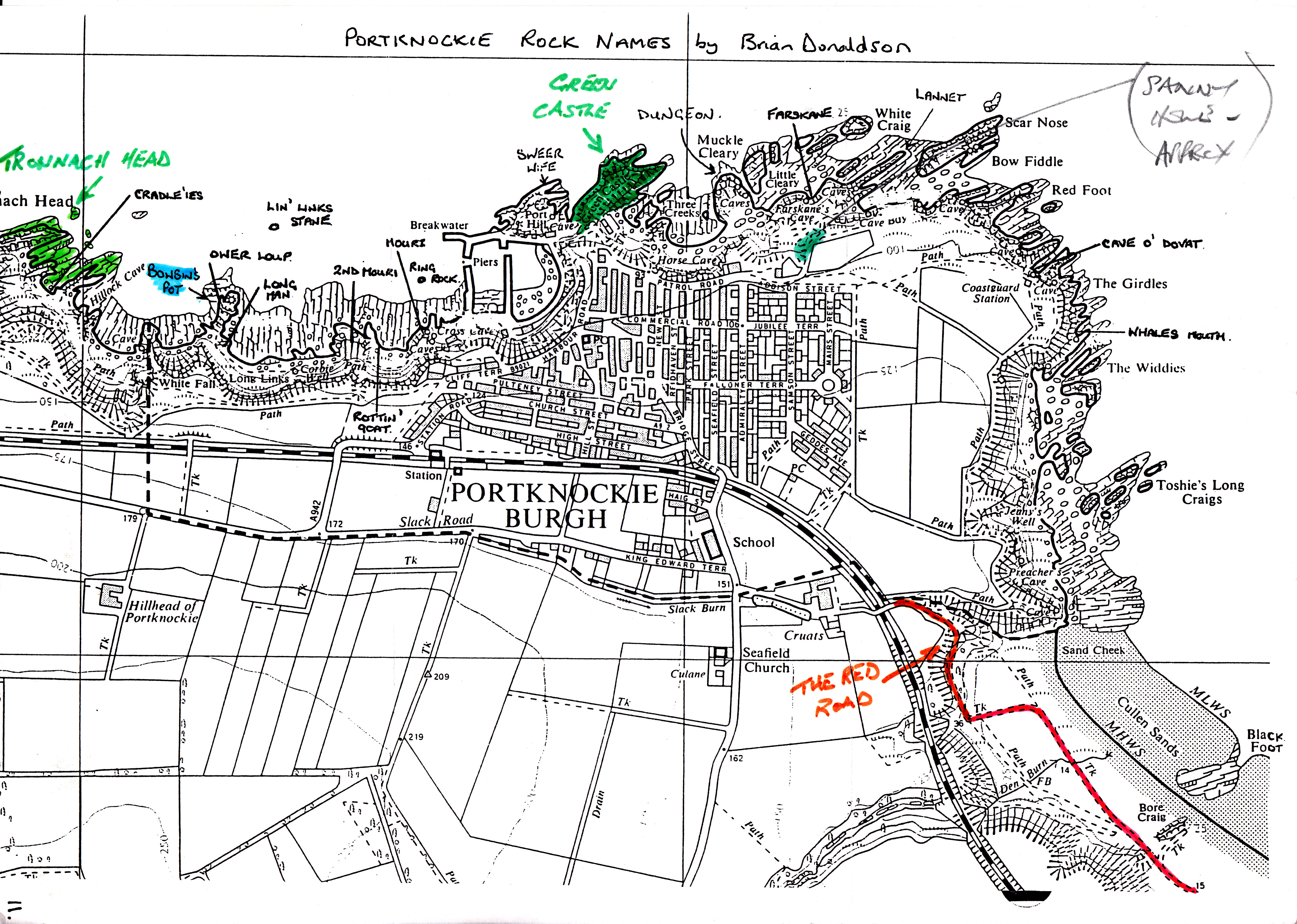

A beguilingly simple and open-hearted song that has not been traced in other collections, nor any news of the composer found in the tight little fisher village of Portknockie near Buckie. Lomax wrote of this song (in the World Library of Folk and Primitive Music: Scotland album), “The genius loci of the Scottish countryside is song, and there is hardly a rock, glen, clachan, or harbor which has not a song in celebration of its peculiar attractions.”

At the entry to Portnockie village, the sign says “Knockers Aye Afloat.”

An intensely local song with no traced composer or publication. The place-names in the last verse are all shown on this map of “Portknockie Rock Names” made by Brian Donaldson. The Reid Road (red because of the colour of its earth), formerly the main track to the neighbouring village of Cullen, is now an access path to the links and beach, crossing Portknockie Golf Course beside Hole 9. A K-nocker is short for a Portknockie resident. The language of the song is that of the North East sea coast.

The remarkable Bow Fiddle Rock is at the top right of Donaldson’s map.

The Barnyards Of Delgaty

This best-known bothy ballad has an apparently simple text with a complex history. The tune and part of the refrain are drawn from a song of love for Lowrie of Linton (which Linton is not known). The vigorous verses link to a more balladic relative called “Jock O Rhynie.” Bothy ballad singer Jock Duncan was surprised about the critical tone of the song. “The Barnyards had aye the best pair o horses—a great ferm toun that.”

“The Barnyards” was a massively popular song, recorded by the Clancy Brothers, the Dubliners, and here by the Ramblers, a “skiffle” influenced group formed by Alan Lomax, Shirley Collins, Ewan MacColl and others. The group’s approach smoothed songs into flatness. Peggy Seeger was also recruited, and commented later that “we didn’t deserve to succeed. And we didn’t.”

G. S. Morris, composer of this theatrical “cornkister” bothy ballad, was born and educated in the city of Aberdeen and worked as a blacksmith and a farmer, then ran a motorcycle business and a hotel in Old Meldrum while singing professionally and recording. Jimmy MacBeath tramped the roads, but was not at all of Traveller stock. Hamish Henderson’s characterisation of the song as a “genuine Tinker’s song” is therefore wide of the mark. Tinkers were nomadic metal smiths, making and mending tin utensils, and perhaps descended from travelling silversmiths of old. Jimmy gets one element of the song story wrong. Usually Annie runs to get the iron pail and crowns Jock with it. Jimmy omits the last verse that he sings on his Tramps and Hawkers Portrait album.

G. S. Morris, composer of this theatrical “cornkister” bothy ballad, was born and educated in the city of Aberdeen and worked as a blacksmith and a farmer, then ran a motorcycle business and a hotel in Old Meldrum while singing professionally and recording. Jimmy MacBeath tramped the roads, but was not at all of Traveller stock. Hamish Henderson’s characterisation of the song as a “genuine Tinker’s song” is therefore wide of the mark. Tinkers were nomadic metal smiths, making and mending tin utensils, and perhaps descended from travelling silversmiths of old. Jimmy gets one element of the song story wrong. Usually Annie runs to get the iron pail and crowns Jock with it. Jimmy omits the last verse that he sings on his Tramps and Hawkers Portrait album.

A Moss is a stretch of boggy moorland. Flanders Moss by Stirling and Solway Moss on the Border were major obstacles impeding invading armies from the south. Now through land improvement much of the Mosses are rich farmland.

The Tinker's Waddin

Before John Strachan’s story, Calum Johnston had told a tale about a drowned stranger coming to a door, but the second part of his story was lost through another tape change.

Later in the 1950s in London, Lomax recorded hours of songs, life stories and traditional tales from Jeannie Robertson, Jimmy MacBeath and Davie Stewart. (This rich material is not in the School of Scottish Studies Archive.) It includes Robertson telling Lomax’s fortune using a card deck—”Oh, what a lot o kisses he’s goin to get,” and “You’ve turned the cradle up and you’ll have that trouble to put up with.” We learn where Davie Stewart was born and how to build a traveller’s “bender tent.” And Jimmy MacBeath tells of his travels to Nova Scotia and wartime France, and his ancestral links to King Macbeth

John Strachan’s vigorous performance of this song was again shredded by tape changeovers, so Christine Kydd has recorded it for us.

Christine has been a stalwart of the Scottish folk scene for over 30 years, performing and recording with others to produce some of Scotland's finest and often award-winning harmony vocal sounds, and also working in numerous teaching, theatrical and community projects and as a vocal coach and choir director.

This song has the first place in Robert Ford’s invaluable 1904 collection Vagabond Songs and Ballads. He reports that “It was written by William Watt, who was born at West Linton, Peeblesshire, 1792, and was author, besides, of the inimitable song of “Kate Dalrymple.” Watt was a weaver to trade. At one time he moved to East Kilbride, where he was Parish Kirk Precentor, leading the congregation in singing in the days before churches installed pipe organs.

Co Siod Thall Air Sraid Na H-eala? [Who Is That Yonder On The Swan’s Road?]

Morag MacLeod writes: “It is no easy task to sing a waulking song on one’s own, since one of its characteristics is the division into solo and choral sections. The chorus usually sang vocables, of which those in this song are typical. Waulking songs were used to accompany the work of shrinking cloth by beating it onto a board in a regular rhythm. They are now unique to Gaelic-speaking Scotland and Cape Breton, Nova Scotia; and, although the practice of waulking cloth stopped in the 1950s, the songs remain popular. They are almost all of anonymous composition; and the themes vary, sometimes even within one song. They are generally taken up with women’s concerns, but again the panegyric element is present, here in praise of the MacNeils.”

The phrase “the swan’s road” is a poetic byname or kenning for the ocean. Viking sagas also used such kennings—e.g., the whale’s path, the gull’s bath.

Co Siod Thall Air Sraid Na H-Eala

Singer and Celtic harp player Maggie MacInnes was born in Glasgow but comes from a long line of Gaelic singers from the island of Barra in the Outer Hebrides and learned most of her Gaelic songs from her mother the highly acclaimed traditional singer, Flora MacNeil.

Maggie has been involved in various groups over the years such as Ossian, Fuaim, Eclipse First and The Maggie MacInnes Band and has travelled widely with her music touring in many parts of Europe, U.S.A., and Canada. She has composed music for BBC documentaries and has acted as music producer and performed in many Gaelic language television and radio programmes.

Maggie has been involved in various groups over the years such as Ossian, Fuaim, Eclipse First and The Maggie MacInnes Band and has travelled widely with her music touring in many parts of Europe, U.S.A., and Canada. She has composed music for BBC documentaries and has acted as music producer and performed in many Gaelic language television and radio programmes.

This praise of a Gaelic hero has survived as a waulking song. Anne Lorne Gillies tells us that Alasdair MacColla was perhaps the greatest warrior in Scottish Gaelic tradition. He was a MacDonald, and led the Royalist Highland and Irish troops during the Montrose campaign of 1644-5. The Marquis of Montrose was fighting to restore to his throne Charles I of the Stuart line, but MacColla wanted to recover from the Campbell clan the Argyll lands that had been held by his family, the Lords of the Isles. MacColla learned his trade as a mercenary soldier in Ireland, and brought his troops and skills back to help win the Battles of Inverlochy and Auldearn.

Alasdair Mhic Colla Ghasda

Anne Lorne Gillies quotes from a contemporary account of the hero: “He was of such extraordinarie strength and agilitie as there was non that equalled or came near him. He was of a grave and sulled carriage, a capable and pregnant judgement, and for his valour, all that knew him did relate wonders of this actions in arms.”

Fuirich An Diugh Gus Am Maireach (Wait Today Until Tomorrow)

Morag MacLeod: “When Mrs. Kennedy-Fraser, the great collector of songs whose work is published in three volumes called Songs of the Hebrides, went to Barra, she could not have achieved what she did without the help of the local teacher, Annie Johnston. Annie was Calum’s sister, and she and Malcolm Johnston were the acknowledged source for the ‘Hebridean Weaving Lilt.’ Mrs. Kennedy-Fraser generally changed rhythms, melodies, and texts—indeed the music most often matched the English-language version—but judging by Calum’s singing, she seems to have resisted that temptation in this instance. He gives us a hint of his skills in vocal dance music (puirt à beul) in the subtle rhythms of this song, keeping the tempo going with ease, but introducing variations in the lengths of phrases as required, to accompany the weaving. The refrain lines are a mixture of vocables, weaving terms, and two translatable lines. ‘A little bird on its nest, it’ll sing along with you. Black mountain, sing black, o horo blackbird.’”

Morag MacLeod: “When Mrs. Kennedy-Fraser, the great collector of songs whose work is published in three volumes called Songs of the Hebrides, went to Barra, she could not have achieved what she did without the help of the local teacher, Annie Johnston. Annie was Calum’s sister, and she and Malcolm Johnston were the acknowledged source for the ‘Hebridean Weaving Lilt.’ Mrs. Kennedy-Fraser generally changed rhythms, melodies, and texts—indeed the music most often matched the English-language version—but judging by Calum’s singing, she seems to have resisted that temptation in this instance. He gives us a hint of his skills in vocal dance music (puirt à beul) in the subtle rhythms of this song, keeping the tempo going with ease, but introducing variations in the lengths of phrases as required, to accompany the weaving. The refrain lines are a mixture of vocables, weaving terms, and two translatable lines. ‘A little bird on its nest, it’ll sing along with you. Black mountain, sing black, o horo blackbird.’”

Macpherson’s Rant

This is the first traditional Scots song I learned and sang in public.

This is the first traditional Scots song I learned and sang in public.

I was born in Inverness, and attended Allan Glen’s School in Glasgow for two years while French teacher Morris Blythman, who wrote songs and poetry under the name “Thurso Berwick” was organising a Ballad and Blues Club during the lunch break. I was for a year too young to attend, so had to hide under a desk when prefects looked in to check. Morris taught old songs and wrote new ones, brought in singers Josh MacRae and Jeannie Robertson to impress and educate us, and took us out to perform. Morris and his wife Marion organised legendary evening ceilidhs in their Balgrayhill house.

My other key influences were Norman and Janey Buchan. She organised me and another young singer, Drew Moyes, to start in 1960 the Glasgow Folk Club, the first commercial club in Scotland. Noisy tramcars rattled by outside in the Trongate, silencing singers. Our first guest was Jimmy MacBeath, his £8 fee was the largest fee he had ever received.

I have at times made a living from music, but, like many people who helped make the Revival, music was for me an enthusiasm rather than a career till I took early retirement, and became busy taking song and songmaking to schools across Scotland and to other countries, as Gallus Productions creating and publishing websites, recordings and books for school use, and much else.

I was honoured to be asked by ACE to help edit several volumes of Alan Lomax’s Scottish recordings in the Alan Lomax Collection on Rounder Records, and in 2015 to be given the Hamish Henderson “Services To Traditional Music” Award. -Ewan McVicar

Jimmy told Alan Lomax in London, ‘He turned out to be an outlaw. He stole sheep and cattle and gave to the poor people. He had 200 men with him. He was a great swordsman, born in Strathspey. They couldn’t get near him, he kept them away with his sword. This woman was washing blankets, she dropped a wet blanket on top of his head, and affore he could get the blanket off they collared him, hand-cuffed him and he was tried before the Sheriff at Banff.’

The King’s Messenger brought the pardon too late, and said ‘Henceforth and onward, that clock shall tell lies’, and ever since the town clock of Banff runs 15 minutes slow, says the story.

MacPherson is said to have been a fine fiddler, and the night before his execution he composed the Rant. Before they hanged him between two trees above Banff he played the tune, and offered the fiddle as a present to anyone who would play his new tune as he danced hanging on the rope. But anyone who took the fiddle would show themselves a friend to him and risk death for the crime of being of traveller stock.

So he smashed the fiddle. The pieces are on show in the MacPherson Clan House Museum in Newtonmore.

Jamie Raeburn

Alasdair was born in Germany, son of a Scots folk guitarist who taught him songs. Alasdair moved to Scotland, and has released a number of solo albums, and frequently collaborated with other musicians and writers, as well as being a member of the Furrow Collective group. He says, “Collaboration is extremely important to me. I reiterate—extremely.”

Robert Ford, an editor and collector of songs, said in 1901 that this song “was long a popular street song, all over Scotland, and sold readily in penny sheet form.”

Robert Ford, an editor and collector of songs, said in 1901 that this song “was long a popular street song, all over Scotland, and sold readily in penny sheet form.”

Raeburn, a Glasgow baker to trade, was sentenced to banishment for theft in the 1840s and transported to the convict cages of Australia. Singers have asserted Raeburn had stolen a loaf of bread to feed his starving family. Ford had a more likely account.

His sweetheart, Catherine Chandler, told the story: “We parted at ten o’clock and Jamie was in the police office at twenty minutes past ten. Going home, he met an acquaintance of his boyhood, who took him in to treat him for auld langsyne.” Detectives appeared, searched the pair, and found stolen property on the friend. “They were tried and banished for life to Botany Bay. Jamie was innocent as the unborn babe, but his heartless companion spoke not a word of his innocence.”

John Strachan Compliments the Audience

The Greig-Duncan Collection has 17 versions of this song, still a favourite with singers. Jessie beats out each word with her foot, and although there is no chorus, the audience is so keen to participate that some begin to hum the tune. Norman Buchan recalled: “The place was electric, and I was surprised, because on the stage was a tiny old lady, less than five feet, dressed in black, fisherwife dressed, and she was chanting out a song called ‘Jamie Raeburn.’ Now, I’d never heard that song before, but I did know what it was. I knew it was a street ballad from a century and a half, or maybe two centuries ago. It was a street ballad that people had sold about transportation, but I had absolutely no idea that people still sang a song like that.” (Radio Scotland, 1994). Buchan went on to inspire young singers and edit the songbooks that fuelled the Revival.

Cairistiona

Alan Lomax, hearing MacNeil sing Cairistiona in the Edinburgh home of the poet Sorley MacLean in 1951, was bowled over: “It was in Edinburgh one June night … that Scotland really took hold of me. A blue-eyed girl from the Hebrides was singing.”

In the song Cairistiona is asked to reply, but cannot, she is dead and ships are coming on the Sound of Islay to collect her body and “bury her low in the ground, beneath the heavy stones forever.”

Anne Lorne Gillies says: “This song—one of the first I learned—belongs to that timeless period of the few centuries before 1745. Although it has survived as a slow waulking song it also seems closely connected to the male work-song genre, the rowing song, or iorram. Certainly it seems to have been composed by a woman—Cairistiona’s foster-mother—who ‘nursed her at her own breast’.”

Maggie MacInnes and and her mother, Flora MacNeil, singing at the 60th Anniversary Ceilidh in 2011. Photo copyright Allan McMillan.

Oran Mor Mhicleoid [The Great Song Of Macleod]

Anne Lorne Gillies says: “‘An Clarsair Dall’ is sometimes described as ‘Scotland’s last minstrel.’ While at school he contracted smallpox, and was left disfigured and blind: it was then that he began to study music seriously—to the detriment of his other studies.” He got musical training in Ireland, and eventually back home “he met Iain Breac, chief of the MacLeods of Dunvegan, who engaged him as his family harper, promising him the tenancy of a farmhouse in Skye in return for his services.” MacLeod also retained a classical poet, a MacCrimmon piper, and a jester. The MacLeod’s family nurse, Mairi Nighean Alasdair Rhuidair, also made songs.

Anne Lorne Gillies says: “‘An Clarsair Dall’ is sometimes described as ‘Scotland’s last minstrel.’ While at school he contracted smallpox, and was left disfigured and blind: it was then that he began to study music seriously—to the detriment of his other studies.” He got musical training in Ireland, and eventually back home “he met Iain Breac, chief of the MacLeods of Dunvegan, who engaged him as his family harper, promising him the tenancy of a farmhouse in Skye in return for his services.” MacLeod also retained a classical poet, a MacCrimmon piper, and a jester. The MacLeod’s family nurse, Mairi Nighean Alasdair Rhuidair, also made songs.

This song was “aimed specifically at Iain Breac MacLeod’s son Roderick, who had been educated in the south and showed little interest in returning to play the role of clan chief.”

The poet says that he left the castle, and he found on the slopes of the mountains the echo of past mirth, the echo of his own singing. and he then has a conversation with the echo about the fate of the House of MacLeod.

In the heyday of the clan system in Scotland, the clan chief was expected to protect his clansmen and servants. His retinue of artists were all obliged to compose propaganda verse and music for their chief. Roderick Morrison, an clarsair dall (the blind harper, c. 1656–1714), was for a time harper to MacLeod of Dunvegan, and when the chief John died, his successor did not fulfil the obligations of his office. Morrison’s song remonstrates bitterly with the new chief, who spends his time in London and his money on foppish clothes. In particular he advises him to look to his predecessor, who had “renown in rich measure, and would never leave Dunvegan without music.” As Hamish Henderson says, the text is based on an imagined dialogue between Echo and the poet.

The John MacLean March

This 1984 recording was Hamish Henderson’s own favourite version of his song. The group was formed by brothers Pete and Gavin Livingstone, pioneering the use of electronics in traditional music. The group is still active, mixing “traditional and original songs with uplifting and exciting arrangements, whilst singing is still a particular strength. A splendid time is guaranteed for all.”

The John MacLean March

The song was written for and sung at the John MacLean Memorial Meeting in St Andrew’s Hall in Glasgow, 1948. Hamish described the tune as a “piper’s version” of an old air, sung as “Bonny Glenshee,” that was further adapted for Cliff Hanley’s “Scotland the Brave,” and for Henderson’s own alternative Scottish national anthem, “The Freedom-Come-All-Ye,” written in 1960 for the Scottish CND (Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament) peace marchers.

Both the “John MacLean March” and the “Freedom-Come-All-Ye” became very popular with Scottish singers in the 1970s. Henderson cuts off to omit his last verse. This song, “Scots Wha Hae,” “Erin Go Bragh,” and the Jacobite songs were the only songs with an explicit political dimension sung in the evening. John MacLean was the great hero of Scottish socialism, “martyred” for his opposition to World War I, and a fiery orator, writer, and organizer. He was the Scottish equivalent of James Connolly of Ireland, both “Socialist martyrs.”

Attempts to identify or trace Mrs Budge, a young Lowlands woman and friend of Hamish Henderson, have been fruitless.

Generally considered Scotland’s own national anthem. Robert Burns wrote the lyric as what “one might suppose to be [King Robert the Bruce’s] address to his heroic followers on that eventful morning” of 24 June 1314 at Bannockburn, when the Scots routed the army of King Edward II of England and regained their independence.

The tune “Hey Tutti Taiti” is said to have been played by the Scots as they marched to the battlefield outside Stirling. The title suggests the taps of marching drummers. The surviving lyric is a drinking song, telling the landlady to tot up her bill.

The French town of Orleans annually celebrates the entry to the town of Joan Of Arc on the 29th April 1429, preceded by her bodyguard of sixty Scottish men-at-arms and seventy Scottish archers led by Sir Patrick Ogilvy of Auchterhouse, hereditary sheriff of Angus, playing the Marche Des Soldats de Robert Bruce. A Youtube search finds several performances by French military bands.

After the Ceilidh

The 1951 Festival was judged a resounding artistic and cultural success, but suffered “a fairly serious financial loss” of £50. The 1952 Festival, however, ran for three weeks, with the Oddfellows Hall again the grand finale. But the involvement of the Communist Party in the organising of the Festival was its downfall, supporters made nervous by McCarthyism dropped out and the 1954 Festival was the last. The effects of the Ceilidhs nevertheless rang out loud and long in Scotland’s Central Belt. Hamish Henderson in Edinburgh began his life-long task of recording and writing about Scotland’s oral culture. In Glasgow Norman and Janey Buchan organised concerts, and he and Morris Blythman edited lyric books and booklets that inspired young singers all across the country.

Remember that this was very much a city-based Revival enthusiasm, in the North East and the Gaeltacht they had never stopped singing and honouring their traditions, not just song but piping, fiddle-playing and country dancing. Alan Lomax up till 1957 continued to mine his Scottish recordings for influential commercial discs and radio and television programmes. Ewan MacColl’s own LP recordings of Scottish songs became another major resource, and the example of his and others’ development of the folk club concept was followed throughout the land.

Here Comes the Folk Revival

All the Ceilidh singers sang unaccompanied, and all bar Jimmy had never been paid for performing. The youngsters who were inspired by them learned from American examples how to accompany themselves on guitars, and began to get paid for performing. Influential folk clubs began in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dunfermline and Aberdeen. Singers who became prominent included Ewan MacColl, Alex Campbell, Josh MacRae, Jean Redpath, Archie and Ray Fisher, Dolina MacLennan, Dick Gaughan, Hamish Imlach, Alison McMorland, Brian MacNeill and Ian Davison. Groups began to emerge—The Reivers, Joe Gordon’s Folk Four, The McCalmans, The Whistlebinkies, The Battlefield Band, Ossian, Ceolbeg. Key record labels were, and are, Greentrax, Temple and Springthyme.

Folk clubs were gradually replaced by festivals, and students developed academic knowledge at the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh, or performance at the RSAMD in Glasgow, and later the Plockton Music School. A few performers moved from folk club beginnings to wider media fame, among them Barbara Dickson, Billy Connolly, Rab Noakes, Eric Bogle. Songwriters proliferated everywhere, and began to produce their own folk-influenced albums, and Plankspanker singers beat on their guitars and carolled the greatest folk hits in the corner of pubs. Slowly the excitement and fierce enthusiasm of the early Folk Revival has ebbed, and “join in singing the chorus” folk events in pubs and small halls have become concert platform performances by remarkably technically skilled younger Scots musicians who tour the world.

Long After the Caelidh

But the 1951 Ceilidh continues to be marked and celebrated. In 2007 accordionist, educator and raconteur Phil Cunningham presented a BBC TV series on Scotland’s Music. Flora MacNeil and I were interviewed sitting in the Oddfellows Hall talking about the Ceilidh. Weeks later I was admitted to an isolation hospital ward, suffering from an odd tropical fever. As I was put to bed I saw a TV on the wall, and asked it be switched on as I thought I was about to be on the screen. The nurses exchanged knowing glances, but I was indeed up there. And in 2011 the 60th anniversary was marked by a ceilidh in the Oddfellows Hall, now an Australian-themed pub, and by the Grace Note Publications book edited by Paddy Bort, “Tis Sixty Years Since, the 1951 Edinburgh People’s Festival Ceilidh and the Scottish Folk Revival.”