Trouble Won’t Last Always was a daily song series launched in 2020 in the early months of the pandemic, featuring recordings from the Lomax collections that spoke to themes of loneliness, isolation, optimism, endurance, transcendence. The selections, spanning from between 1933 and 1983, draw on a diversity of Lomax recordings of American traditional music: sacred and secular, ironic and straightforward, humorous and grave, with topics spanning the occupational, political, romantic, domestic and existential. Originally posted on Instagram and YouTube, these performances are now gathered here in a more permanent home to comprise the inaugural exhibit of the Lomax Digital Archive. Selected and annotated by LDA curator Nathan Salsburg; introduction by Dom Flemons, the American Songster; and image research and lyric transcription assistance by Matt Gold.

-April 2021

The poetry of “Life Is Like That” by Memphis Slim is all the more poignant now that we are living through a worldwide pandemic. Not only has every part of modern life been affected by COVID-19 but the cultural and social movements surrounding Black Lives Matter have caused people to rethink the systems that created racial oppression and injustice. What can be said in these hard times that have no clear end in sight? Over the millenia, human beings have used music to move each other to action. Sometimes the music is a voice; other times it's an instrument that takes the lead. There are moments when the voice of the singer is only a means to convey the lyric, not bothering to sound “good” by classical standards. Other times, especially in situations where the listener is NOT a fluent speaker, the voice can serve as the most robust expression a single individual can offer to another through song.

Sometimes you'll be helpless,

Sometimes you'll be restless,

Well, keep on strugglin'

So long as you're not breathless

Because life is like that—well, that’s what you got to do

Well, if you don’t understand, peoples, I’m sorry for you.

Messages of love, work, politics, faith, social advocacy and life’s basic experiences of ups and downs can dictate everything that a song can mean to a singer. The audience is also actively participating as well, confirming and reassuring the singer to present certain songs and aesthetics that define their culture. In just a few minutes, “Life is Like That,” presents a complex portrait of blues and its cultural role in the Mississippi Delta.

On March 2, 1947, after a concert performed at New York City’s Town Hall, folklorist Alan Lomax sat down with professional blues singers, Memphis Slim, Big Big Broonzy and John Lee “Sonny Boy” WIlliamson and asked them about the origins of the blues. The recording technology and location, a Presto Disc Recording Machine in the Decca Records studios, proved to be an easy environment for Alan to document the songs and stories of these icons. The environment proved so comfortable that as they began to record their low-down blues they began to expound upon the situations in which the blues was born.

While it may be hard to imagine in the modern era, it was forbidden for a black person to speak out about the oppression of segregation. To do so would put yourself as well as anyone connected to your community at risk if the news through the grapevine said that you were causing “trouble.” Boldly, each singer played, sang and spoke about this issue despite the consequences. In their own ways, each spoke with razor sharp commentary of racial oppression, economic suppression and cultural erasure. All three men had grown up in the Deep South and they all pursued a career in music mostly as a means of escaping the rural environment of their birth. Residing in Chicago, their down-home flavor gave voice to a displaced community running from the hard aches of the Jim Crow laws and looking for a better life. Now in the 1940s, each was much more well-known and still in peak form. Their commentary, as issued on the album “Blues In the Mississippi Night” in 1959, provided context for people outside of the culture as told by the singers themselves. That album was deemed so controversial by all parties that it was originally issued with anonymous crediting even though anyone remotely familiar with these popular blues singers will recognize their distinct voices and playing styles.

The harsh reality of being helpless, restless and possibly in danger runs across all of the songs on this playlist, because whether it is 2020 (or any year in the future or the past), these feelings expressed through songs are universal ways to cope with the world around us. It’s a joyous, sorrowful, and soul-building series of recordings that remind us that truly “Trouble Don't Last Always.”

- Dom Flemons, The American Songster

Life Is Like That

We Shall Not Be Moved

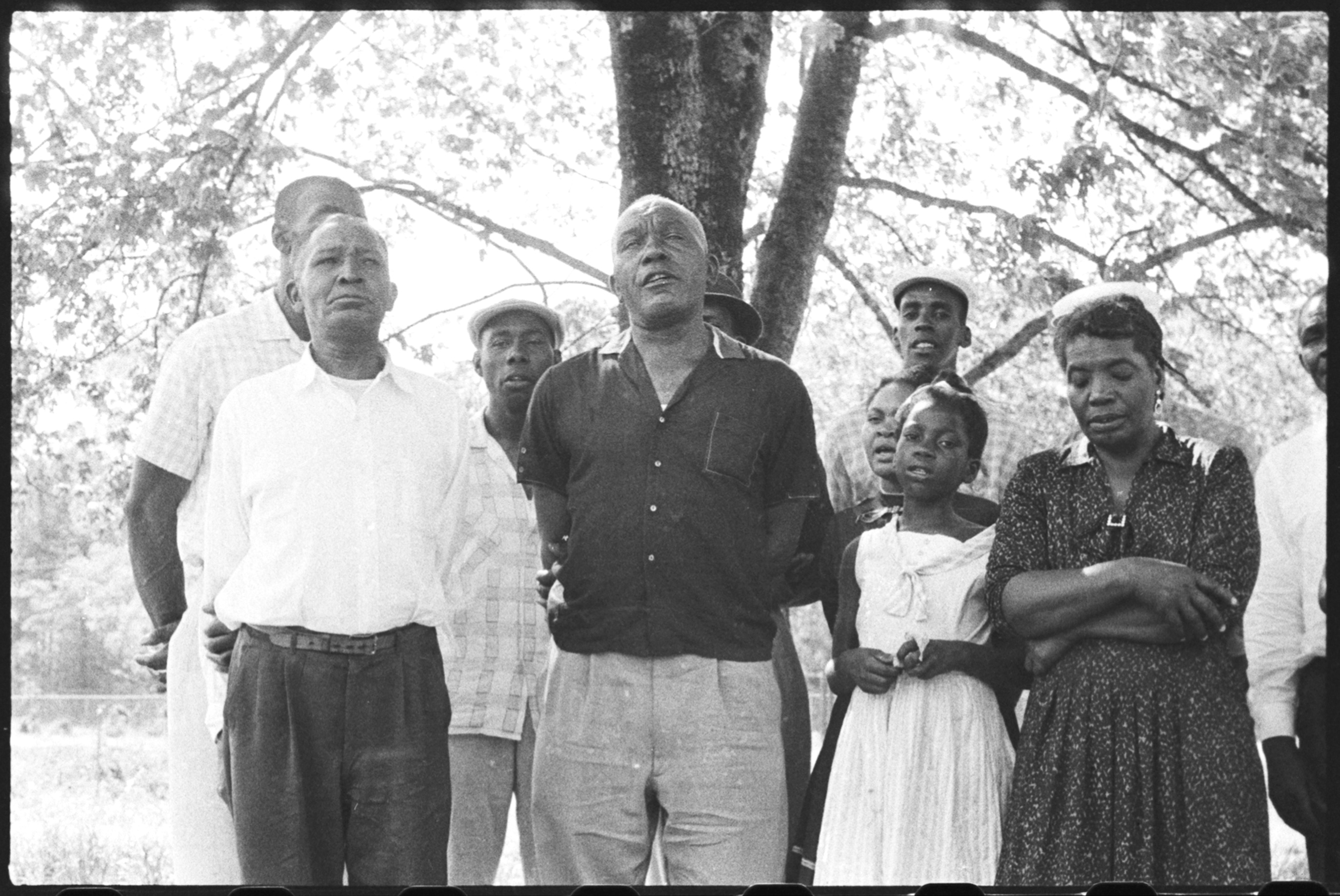

Katherine Trusty, a teenage daughter of miner and labor activist Brother Elihu Trusty, sings the protest version of the spiritual "I Shall Not Be Moved," which originated with the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union in Arkansas in the early '30s. (Rev. A.B. Brookins, a Black preacher from Marked Tree, Ark., has been credited with the spiritual's introduction to the STFU.)

Sorry, Sorry for to Leave You

Nothing is known of Ms. Threadgill or Ms. Johnson beyond their powerful sanctified performances documented by Lomax and Jones at the Mohead Plantation on Moon Lake, toward the end of the Fisk University/Library of Congress survey of life and culture in the Mississippi Delta. (See here for the complete collection and its background.) Our organization visited the Mohead Plantation in 2013 and hoped to find the church-house still standing; all but two of the former tenant residences and other buildings had, however, long been razed.

Coming Through: Voices of a South Carolina Gullah Community (U. of South Carolina Press, 2008) provides this detail of Maybank’s biography: “According to the 1910 census, Maybank was a literate carpenter who owned his own home. The 1930 census lists Maybank’s age as 56 and his wife’s [Celia] as 44.”

Aaron McCollough offers further context for the song:

Mike Maybank led the crew that paved Highway 17 through Murrells Inlet in 1934 and also the Works Progress Administration ditching crew responsible for excavating a network of ditches to drain the inland swamps of Waccamaw Neck. Draining the formidable Mission Swamp of Murrells Inlet was one of the ditchers’ primary tasks. The ditches Maybank’s crew dug for the W.P.A. are still in use, draining into the creek. (From the liner notes to Deep River of Song: South Carolina, Rounder Records, 2002.)

Right Down Here

Bessie Jones was one of the most popular performers on the 1960s and '70s folk circuit, appearing either solo or at the helm of the Georgia Sea Island Singers at colleges, festivals, community centers, the Poor People's March on Washington, and Jimmy Carter's inauguration. Alan Lomax first visited the Georgia Sea Island of St. Simons in June of 1935 with folklorist Mary Elizabeth Barnicle and author Zora Neale Hurston. There they met the remarkable Spiritual Singers Society of Coastal Georgia, as the group was then called, and recorded several hours of their songs and dances for the Library of Congress. Returning 25 years later, Lomax found that the Singers were still active, and had been enriched by the addition of Bessie Jones, a South Georgia native with a massive collection of songs going back to the slavery era. He invited her to New York City in 1961 to record her “oral biography,” carried out over three months and some 50 hours of tape. (Lomax’s then-wife Antoinette Marchand can be heard as interviewer in many segments.)

Dangerous Blues

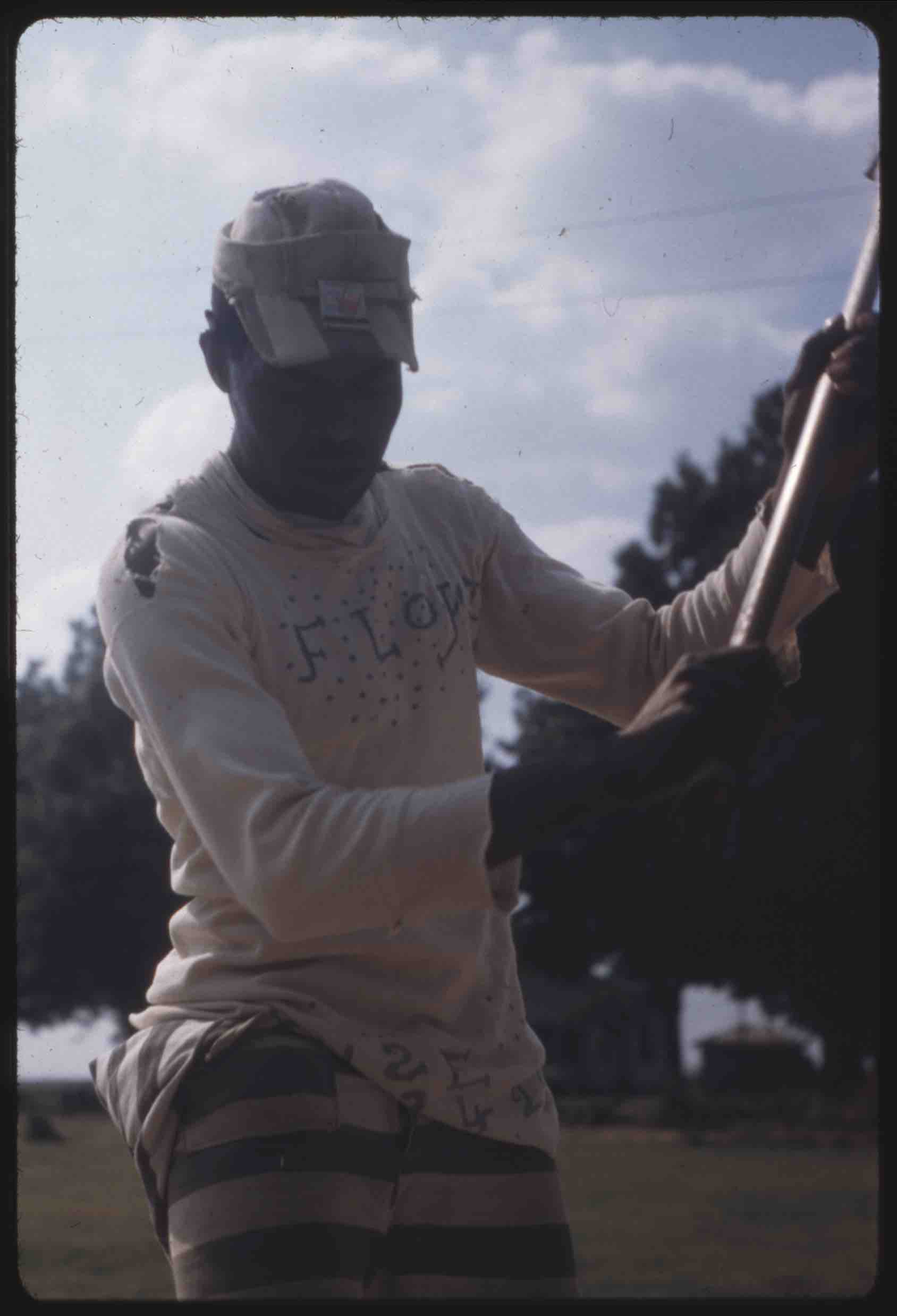

Parchman Farm (Mississippi State Penitentiary) prisoner Floyd Batts sings a variation on "Dangerous Blues," or "Danger Blue," a theme sung by Black inmates throughout the Southern prison-farm system. Nothing is known of Floyd Batts’ origins, the circumstances of his incarceration, or when (or) if he was released from Parchman.

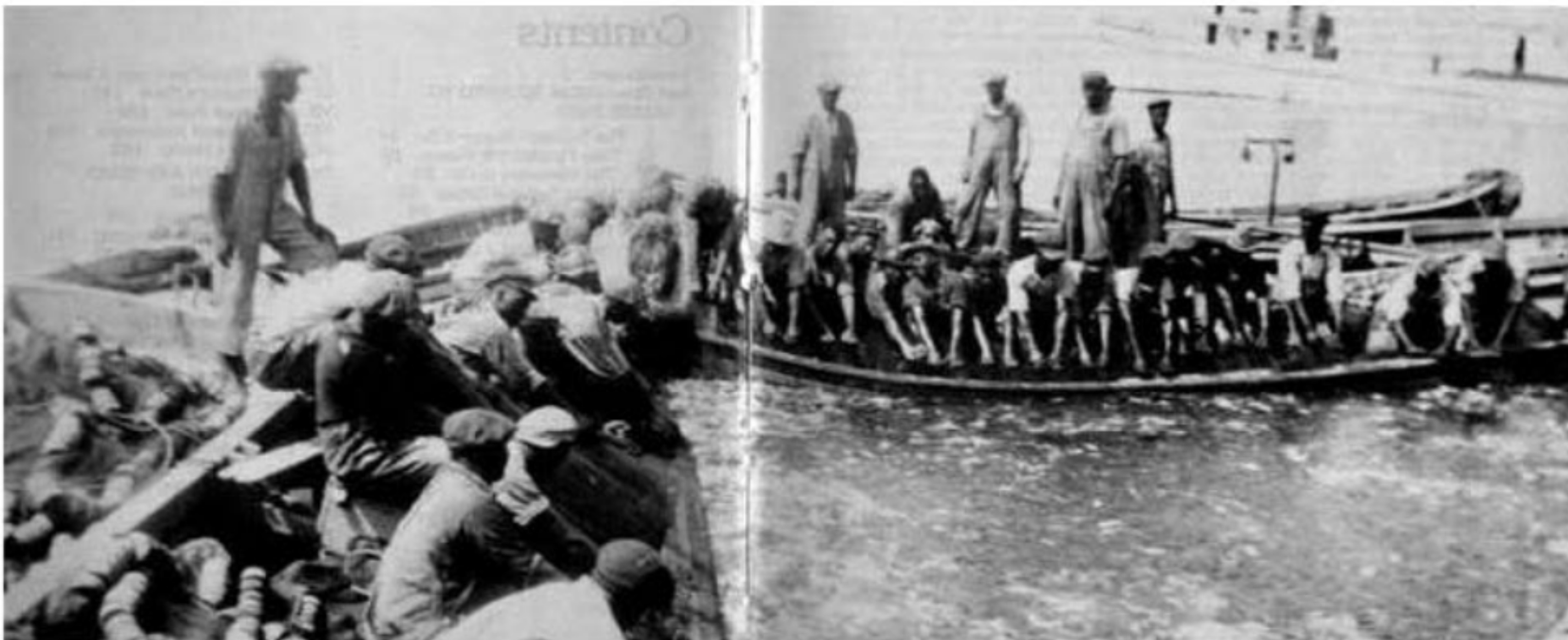

The Bright Light Quartet worked hauling nets aboard the fishing packets that plied the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic, from Long Island to the Gulf of Mexico. Menhaden, a bony, inedible fish processed for its oil and its use in livestock feed, provided well-paying work to African American men in the Northern Neck of Virginia and the Outer Banks of North Carolina—the industry's two centers of production being in Reedville, VA, and Beaufort, NC. When the Quartet weren't singing net-pulling chanties at work aboard the trawlers, they gave performances in churches throughout the region, and occasionally as far away as New York City.

Menhaden fishermen's chantey medley

Wondrous Love

Sitting at my Window, Sad and Lonely

The 18 songs Devall sung for Lomax were the last recordings John would contribute to the Library of Congress’ Archive of Folk Song. Devall had cut two earlier unaccompanied sides in Dallas in 1929.

Family Circle

Turner Junior Johnson was a blind singer and harmonica player whom Lomax and Lewis Jones met performing on the streets of Clarksdale. Lomax describes meeting him in his diary:

I met him Sat. night [July 18] on the street in the Negro section, blowing his harp and shaking a little tin can for his collection of nickles. He has been blind since he was 16 years old when he had the swimming in the head and the wagon ran across the back of my head—both wheels—took me a solid week to loose your sight [sic]. “I suffered with a swimmin’ in my head when I was comin’ up. When I first lost my sight, I didn’t eat nothin’. My sister come and help me—my baby brother helped mama. My father was dead.” He’s the only musician in the family.

Johnson gave his place of birth as “round Senatobia,” in the Mississippi Hill Country and, upon finishing this piece, credits multi-instrumentalist Sid Hemphill (who was also blind) as his source, thus bringing this great performer and composer to Lomax and Jones’ attention. (The disc cuts out with Johnson giving the two directions to Hemphill’s home.) They would record Hemphill and his band several weeks later at a picnic in Quitman Co., Mississippi.

Sitting on Top of the World

Oh Death

Adele "Vera" Ward Hall, despite her exquisite singing abilities and her extensive repertoire, worked all of her life as a washerwoman, nursemaid, and cook. She first came to the attention of John A. Lomax in 1937, when Ruby Pickens Tartt, folklorist and chair of the Federal Writers' Project of Sumter County, Alabama, introduced them; Lomax recorded Hall during three separate sessions in 1937, 1939, and 1940, writing that she had "the loveliest voice I have ever recorded." She sang Baptist hymns with her cousin Dock Reed and other Livingston friends like Jesse Allison, but she was also willing to record blues, ballads, hollers, and "worldly songs" such as "Stagolee” and "John Henry” learned from her friend Rich Amerson (and forbidden by her family).

Job, Job

I’ll Get A Break Someday

This last recorded iteration of the Memphis Jug Band (who had made their first records in 1927) featured original members Charlie Burse and Will Shade, performing here a song first cut by Tampa Red in 1934. Personnel was given as Shade, vocal and acoustic guitar; Burse, guitar; Robert Carter, electric guitar; and Dewey Corley, bass/kazoo, along with Eugene Smith, who was either nicknamed “Whiskey” or brought it to the session. (Burse and Shade made later recordings in the 1960s but none of them featured a jug.)

Roll On, Buddy

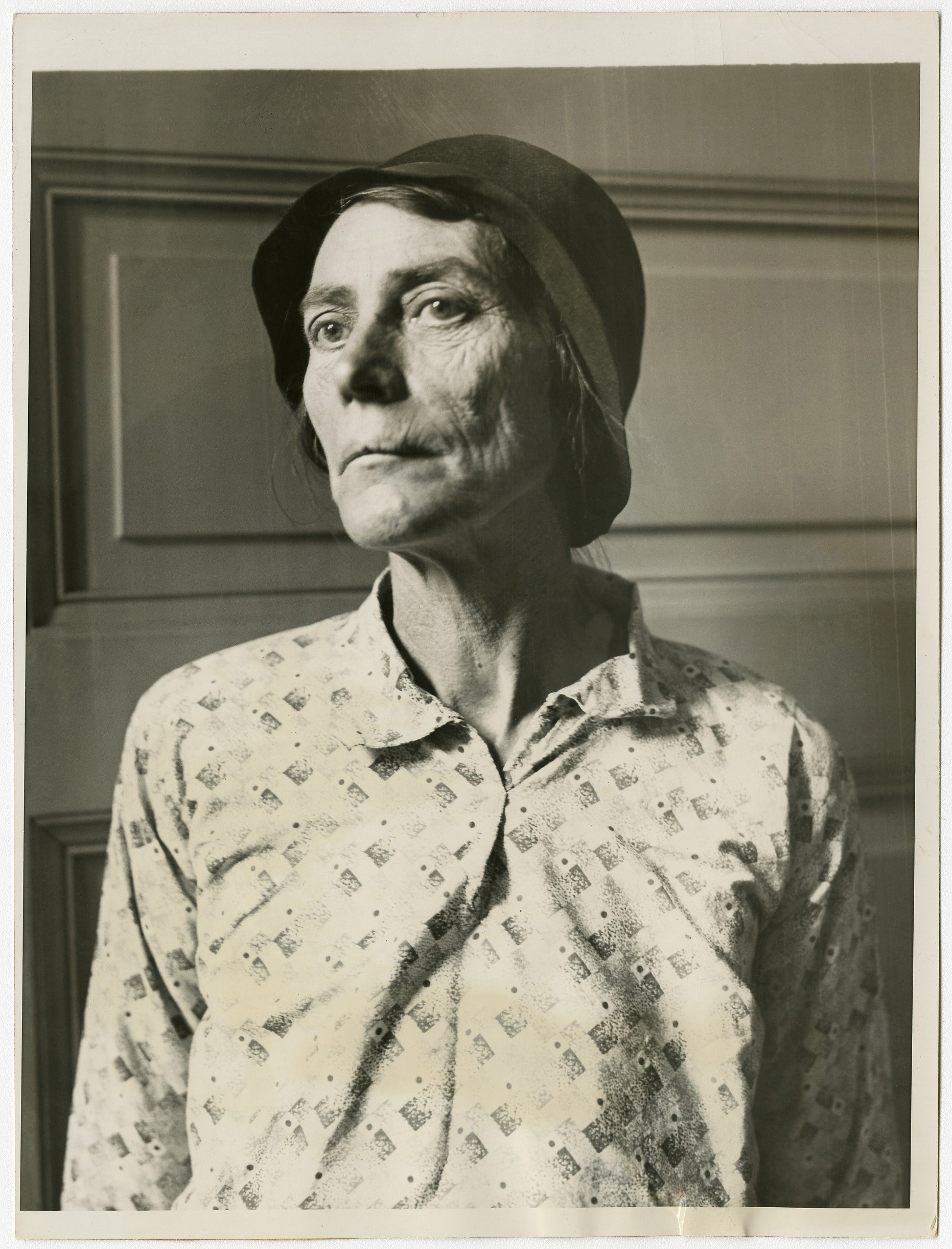

The song and stories of Mary Magdalene Garland Mills Stewart Jackson, better known as Aunt Molly Jackson, were rooted in her life experiences in eastern Kentucky’s Clay, Laurel, Bell, and Harlan Counties. Born in 1880, she was a coal miner's daughter, married a miner (Bill Jackson) and became a mother, midwife, songwriter and labor activist agitating on behalf of the National Miners Union (NMU) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). She was once jailed in Harlan County for union organizing activities. She traveled to New York City in December 1931 to promote the cause of and raise money for striking Harlan County coal miners and stayed there throughout the 1930s, in part fearing reprisals back home. We are pleased to take this opportunity to present the entirety of Jackson’s Library of Congress recordings—she has recorded at various times by John Lomax, Alan Lomax, and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle, beginning in 1935 when Molly was 55 and extended over a four year period. (She also made a single phonograph record for the Columbia company in 1931, and was recorded by Alice McLerran at her last home in Sacramento, California, in 1959 and several months before she died in 1960.)

I Got Trouble

Belton Sutherland was born on Valentine’s Day, 1911, into a farming family in the Camden area of rural Madison County, Mississippi. In the 1930s he played guitar behind a popular local fiddler named Theodore Harris, “wasn’t no maybe-so about it: the best fiddle player that ever went through here,” as Belton told Lomax, Long, and Bishop, but their partnership ended when Sutherland followed the tens of thousands of his fellow Black Mississippians in the Great Migration north to Chicago. He’d stay there 37 years before moving back to Madison County, where he was able to buy himself 40 acres, twenty miles from those of his friends Clyde and Bea Maxwell—where the trio filmed him in 1978. Everything about Sutherland’s approach is jaw-dropping: his gravelled voice; his baldly aggressive lyricism (“Killed the old grey mule, burned down that white man’s barn”); and the relentless, propulsive rhythm his strumming thumb and tapping foot beat out in unison. “I definitely know sometimes if I take that notion, and have that feeling, I can play a guitar pretty good,” he confessed. It’s the cigarette hanging rakishly out of his mouth, though, that Worth Long calls attention to: a clue that Sutherland was foremost a drummer. When Long first met him, Belton was drumming in a trio—despairingly never documented—and is if that weren’t enough, Worth continues: “And he blew the shit out of the harmonica! But Alan was tired…” No evidence of these talents survive. In fact, the six pieces he recorded this September night constitute the entirety of Belton Sutherland’s recorded output.

Barres de la Prison

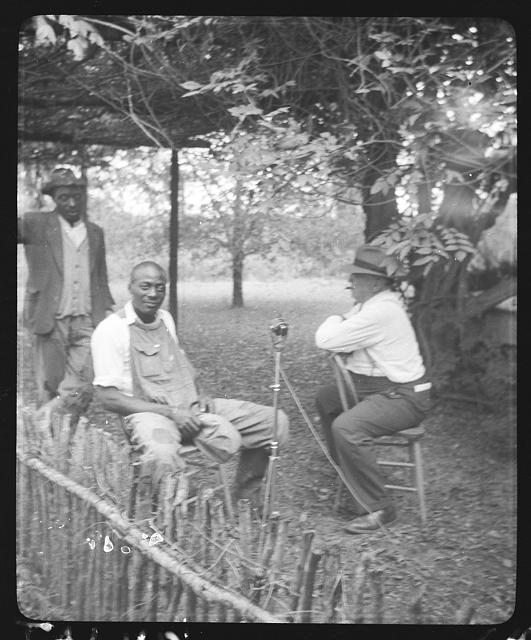

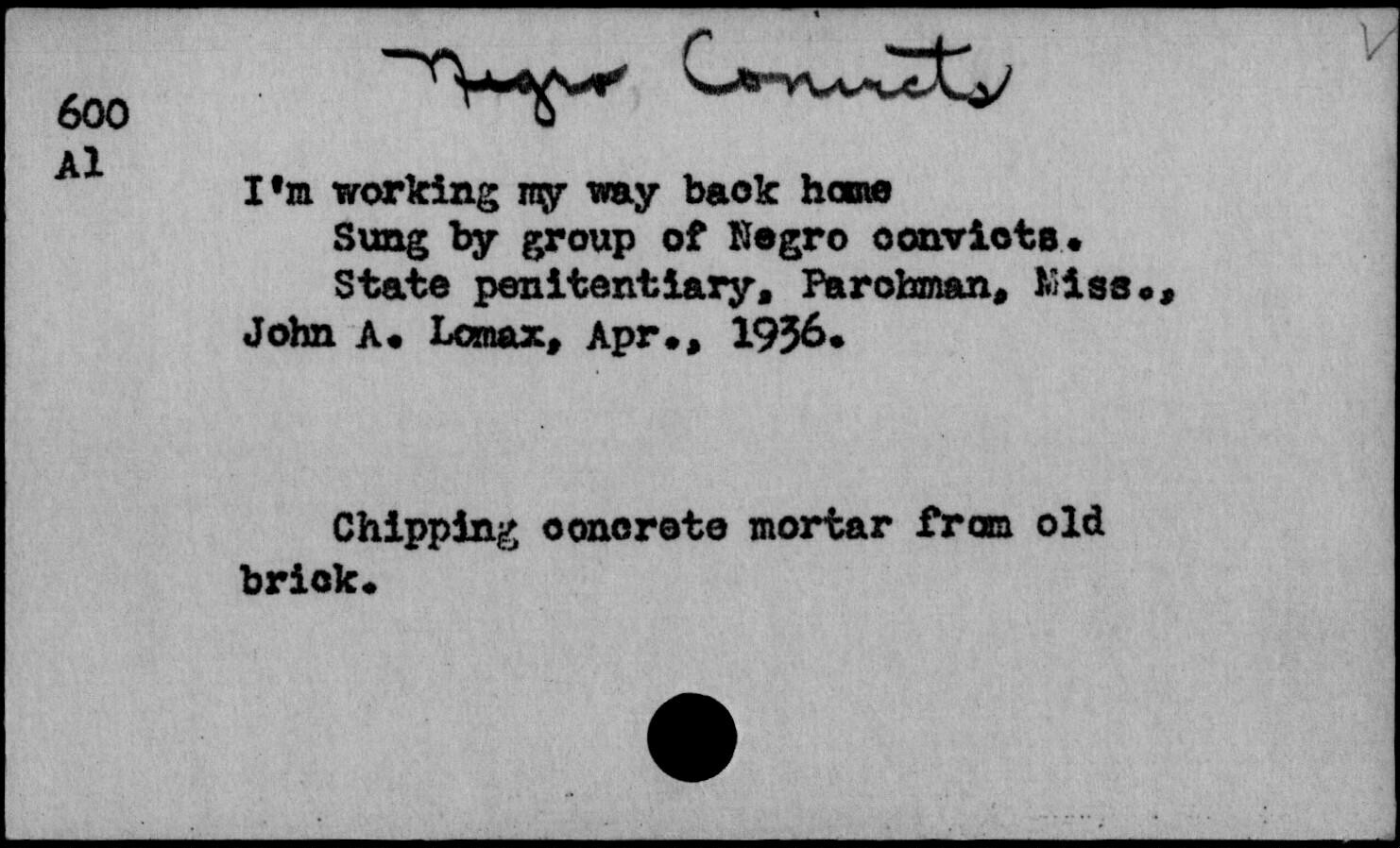

Working My Way Back Home

And Must This Body Die?

The somber lined-out hymnody of the Old Regular Baptists—in which a leader "lines out" a verse for the congregants to sing back, in their own fashion and their own time—is a rare hold-over of a once-widespread singing style that’s only getting rarer. Dating to the middle of the seventeenth century, lining was practiced throughout the British Isles and New England, but by 1959, they were being sung in just a handful of remote locales: in Presbyterian churches of Scotland’s Gaelic-speaking Western Isles; among more traditionally minded African-American Baptist (and, occasionally, Methodist) churches in the deep South; and in the Old Regular Baptist meeting-houses of the Central Appalachians.

Members of this Tidewater Virginia gospel group unidentified at the time of the recording, in May of 1960. (A Norfolk group under this name made some records later in the '60s, which included the names of the following singers: Clyde Burston, Percy Griffin, Jake Chambers, and Charles Russell. If anyone can confirm their involvement in Lomax's session, please let us know. Photo is culled from the group's Discogs entry, as Lomax took no pictures during the session.)

Alan Lomax later recalled: "I made this record in a little Baptist church in the slums of Norfolk, inviting a group of neighborhood girls to listen. When they began to clap and stomp out an accompanying rhythm, the Peerless Four took off and flew. Somewhere in the middle you can hear the two leaders swapping their rhythmic parts with every phrase, a feat I have [sic] never before heard quite equaled at this tempo."

Jean Thomas, who called herself "The Traipsin' Woman," was, among other pursuits, a song collector and the founder of the American Folk Song Festival. She arranged this 1937 session for John Lomax, featuring some of her Eastern Kentucky "discoveries," which included Day. Thomas worked as Day's manager, rechristening him "Jilson Setters" and calling him "The Singin' Fiddler of Lost Hope Hollow." Day recorded several records of Kentucky fiddle tunes for the Victor company in the late '20s, and was the subject of two of Thomas' books. Their partnership is a fascinating case study in the ethical complications involved in presenting and promoting "authenticity." (Although Thomas credits Day with this song’s composition, it seems likely to have been written by a moralizing Victorian-era songster.)

For more on Thomas and Day, visit appalachianhistory.net.

The Blind Man's Lament

Cold Mountains

Alan Lomax considered Texas Gladden one of the three best ballad singers he ever recorded (the others being Almeda Riddle of Arkansas and Scotland’s Jeannie Robertson). He wasn’t alone in admiring her—several folklorists had collected her songs in the 1930s, and, two years after hearing her sing at the White Top Festival in 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt invited Texas and her brother Hobart Smith to perform at the White House. Although her singing had been diminished by ill-health, she recorded a number of shorter pieces for Lomax in 1959: love songs, some ballad verses, and lullabies sung to her granddaughter Cynthia Tuttle, whom Texas called “Baby Cindy.” Despite her popularity, she was never much inclined to travel for the concerts folk revivalists were putting on in the mid-’60s. Besides, when Lomax wondered why she’d never made much “professional use” of her singing, she replied that she’d “been too busy raising babies! When you bring up nine, you have your hands full. All I could sing was lullabies.” Texas died in 1967.

Among the members of the Spiritual Singers of Coastal Georgia that Lomax met in 1935 (see Bessie Jones’ track above) were fisherman Henry Morrison and Big John Davis, a former sailor and stevedore, and a singer with an extensive repertoire of chanties, roustabout songs, slavery-era ring-plays, and religious material. Davis told Lomax then that he knew six separate songs concerning Moses but joked that "if I give them all to you now, you won't come back." And Alan recalled that when he did return, "twenty-five years later with a stereo rig adequate to record this multipart music, I was greeted as an old friend." This spiritual, exhorting Moses not to lose heart as Pharaoh pursues him, was one of two Moses-related songs Lomax recorded in 1959 and is of obvious slavery-era origins.

Moses Don't Get Lost

A song performed by quarryman, lumberman, fiddler, and folk-singer Grant Rogers, who reported that the melody was his but the lyrics learned from a "colored gentleman" in New Jersey. Learn more about Rogers at the Grant Rogers Project, an initiative to preserve and promote the expressive culture of the Western Catskill region of New York State.