The Lomax collections reflect a vast variety of human experience—from the sacred to the profane, from the rural to the urban, and from the public square to the domestic scene. The Lomaxes recorded lullabies all over the world, creating a record of the universality of these particularly intimate moments between parents and children. In this exhibit, we’re presenting some of our favorite lullabies from the collection alongside new interpretations by contemporary musicians.

Go to Sleepy Little Baby

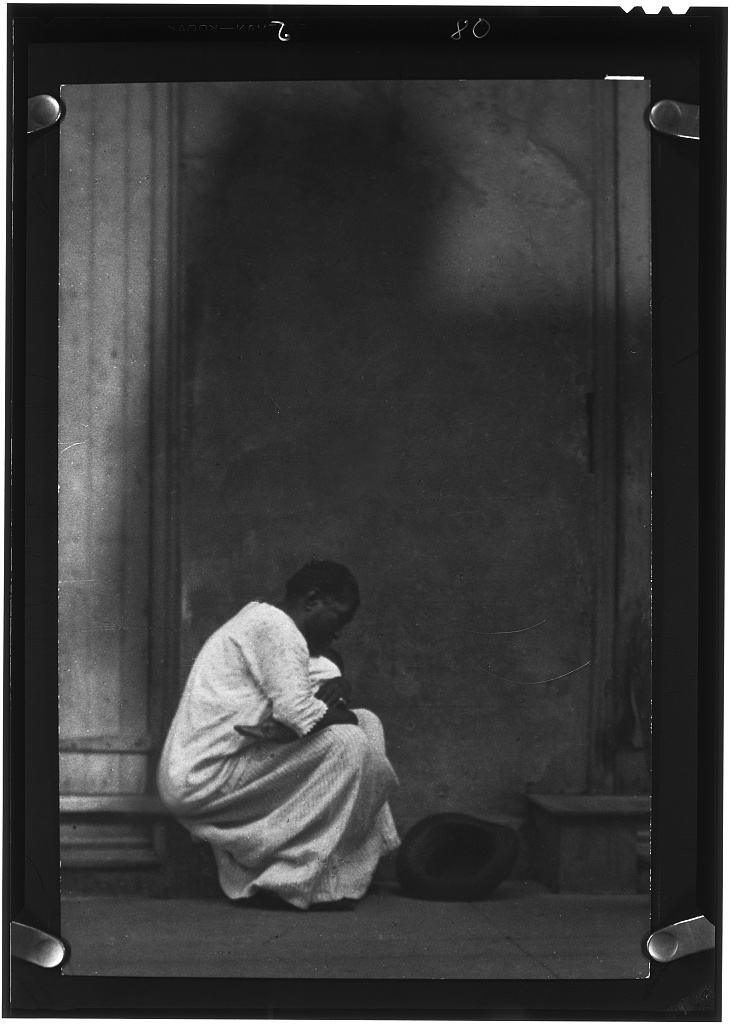

Alan Lomax first visited the Georgia sea island of St. Simons in June of 1935 with folklorist Mary Elizabeth Barnicle and author Zora Neale Hurston. There they met the remarkable Spiritual Singers Society of Coastal Georgia, as the group was then called, and recorded several hours of their songs and dances for the Library of Congress. Returning 25 years later, Lomax found that the Singers were still active, and had been deeply enriched by the addition of Bessie Jones, a South Georgia native who knew a breathtaking quantity of songs, many of which dated to the slavery era, and who had moved to island shortly after Alan’s first visit. While Jones had worked as a cook, a housekeeper, and a migrant agricultural laborer, she had extensive experience as a midwife, and was particularly drawn to caring for the very old and the very young. Her repertoire of children’s game songs, play songs, riddles, “jumps,” and lullabies was immense.

Throughout the 1960s and early ‘70s, she and Alan’s sister Bess Lomax Hawes collaborated on a collection (published as Step It Down in 1972) of 70 of Jones’ game songs, “plays,” and other activities and melodies for children. Jones had served as a midwife and a caregiver for many mothers and children over the years. As she told Alan Lomax in an interview in 1961: “I love so well getting the babies to sleep.” Bessie learned “Go to Sleepy” from her mother, and knew it specifically as a rocking song.

Sandy Rogers didn’t start making music until she was squarely into adulthood: she’d graduated college (UC Davis, with a degree in psychology), gotten married, had a kid, gotten divorced. “I was at a point where I was just sitting up there in Davis with nothing to do,” she told the Los Angeles Times in the mid 1980s. “I finally got a piano and started fooling around with music.” She was momentarily poised on the brink of some kind of stardom then, having contributed her monumental “Let’s Ride” to the soundtrack for Fool for Love, Robert Altman’s 1986 film adaptation of the play by the same name by her brother Sam Shepard. The song would turn up again in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs in 1992, but it wasn’t until 1997 that Rogers finally released her first solo album, Green Moon. Although only one other album (Wonderin’) has followed, she’s steadily performed since, her unforgettable voice deepening and weathering, and still stopping listeners in their tracks. Sandy kindly recorded her version of “Go to Sleepy Little Baby” for us here.

Go to Sleepy Little Baby

"I sang to babies so much, just all church songs, you know, just sing and sing and sing, just anything I could think of. And at last one day, I jumped off on "Casey Jones." Mama come to the door, she say, "Well! I never heard nobody put no babies to sleep on 'Casey Jones'!" I had just sung on out ... I had just sung and sung and sung, and he wouldn't go to sleep, so I got off on "Casey Jones"! I sing all manner of songs…"

Didn't Leave Nobody But the Baby

Sidney Hemphill Carter was the daughter of Sid Hemphill, legendary multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, bandleader, and musical patriarch of the Mississippi Hill Country. Lomax had recorded Sid and his band in 1942, but when he returned to Panola County in 1959 he worried that he'd find, as he had on many other occasions, "that the best people had passed away or withered and their communities had gone to pieces." However, not only was Sid "still alive and fiddling," as Lomax wrote, but his extended family were on hand to contribute performances of their own. Ms. Carter sang sacred songs, snatches of lyrics to old-time dance tunes (“reels,” locally), and the lullaby “Didn’t Leave Nobody but the Baby.” It was this recording that was arranged and expanded upon by Gillian Welch and T. Bone Burnett for inclusion in the soundtrack to the Coen brothers’ 2000 film O Brother, Where Art Thou?, where it was performed by Welch, Emmylou Harris, and Alison Krauss.

Sylvania, Georgia native Beareather Reddy – vocalist, songwriter, actress, producer and radio host – is deeply entrenched in the contemporary Brooklyn blues scene as a self-proclaimed "Champion for the Blues." Here she provides us with a heart-rending reading of Sidney Hemphill Carter's “Didn't Leave Nobody But the Baby.”

Listen to her own experiences with lullabies or read the transcript.

Adele “Vera” Ward Hall (1902–1964), who worked throughout her life variously as a field hand, laundress, nursemaid, and cook, was regarded by the Lomaxes (though certainly not only by the Lomaxes) as one of America’s greatest singers. She first came to the attention of John A. Lomax in 1937, when Ruby Pickens Tartt, folklorist and chair of the Federal Writers’ Project of Sumter County, Alabama, introduced them. Lomax recorded Hall during three separate sessions in 1937, 1939, and 1940, writing that she had “the loveliest voice I have ever recorded.” She sang Baptist hymns with her cousin Dock Reed and other friends in Livingston, in Sumter county, but she was also willing to record blues, ballads, and “worldly songs” such as “Stagolee,” “John Henry,” and “Boll Weevil,” learned from her friend Rich Amerson, and forbidden by her family.

Alan Lomax met Hall in 1948, when he arranged for her and Reed to come to New York City for the American Music Festival. This time together resulted in six and a half hours of recordings and the raw material for a biography which Lomax published in The Rainbow Sign (1959). In that book, in which Vera was called “Nora” to protect her identity and honor her confidences, she speaks frankly of the immense hardships of her life, but also of her desires, her joys, and her deep religious commitment. Hall had two children, although she spoke little of them to Lomax, and no information about them was recorded. This lovely little lullaby, however, must have been intimately known to them.

Samoa Wilson came up in the Boston folk scene, under the wing of jug-band and folk legend Jim Kweskin. Now part of a new generation of New York folkies centered around Jalopy Theater, she was invited by Eli Smith (founder and director of the Brooklyn Folk Festival and Jalopy Records) to contribute to our lullaby project.

She shared these thoughts:

"I think of lullabies as forming a sort of traceable matriarchal lineage. There were Italian lullabies that my mother would sing to me, that she had learned from her mother. I can't remember the words or the melody, but I remember there was a part where she would tickle my nose and say nonsense words. I do remember her singing "All the Pretty Little Horses" to me as she was putting me to bed, and I would sing that one to my own daughter later on, along with "Baby Mine" from the Dumbo movie. I also sang a version of "The Ballad of Barb'ry Ellen" that I learned from the John Jacob Niles recording. When I was a child, we listened to that one frequently. I sang it to my daughter because it has so many verses, it would certainly lull her to sleep eventually. She will occasionally sing it herself now, with all the verses, at family gatherings, if you beg her enough. It must be something to do with that drowsy suggestive psychological state, that lets repeated words sink in and embed themselves in memory. My mother was hollering "Irene Goodnight" as she was giving birth to me, and she sang it to me daily henceforth. That song, with the tall tale that goes along with it, is the way I end almost every performance I give."

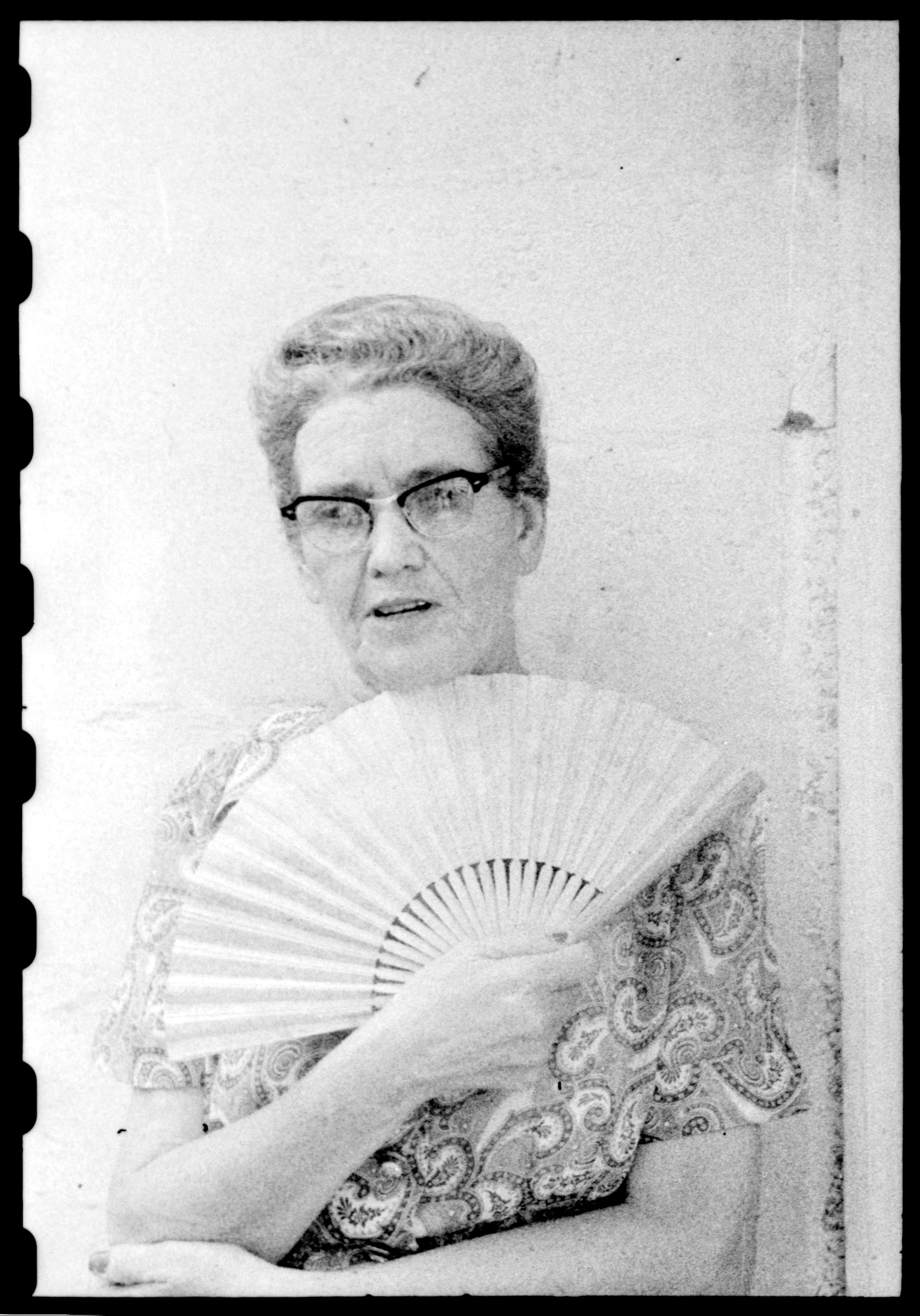

Shirley Lomax Mansell, Alan’s older sister, was recorded by her father John A. Lomax during the latter’s field trip through Texas in the spring of 1939. She performed for John and her stepmother Ruby T. Lomax (whom everyone called “Miss Terrill”) several discs’ worth of childrens’ songs that she had learned from her own mother, the late Bess Brown Lomax, John’s first wife.

From Ruby T.’s field notes from that trip:

Shirley Lomax Mansell...not only speaks for herself here, but for practically every other Southern girl who has ever been rocked to sleep or who has ever sung to her own babies.

All the Pretty Little Horses is a family song. There is not a time when I do not remember it. I am sure it was Grandmother Brown's song; from our mother it now belongs to her four children. Grandmother did not often sing anything but hymns, and those mostly on Sunday afternoons when she rocked back and forth in her little straight, cane-bottomed rocker, alone in her room. Grandmother did not believe that on Sunday people should do anything but attend Sunday School, then church, then read the Bible until time to go to evening services. Her disapproval of our Sunday afternoon walks, when the children from all the neighborhood gathered to explore the woods, or "walk through to the Dam", caused her to shut herself into her room and rock and sing, and I am sure, pray for forgiveness for us all. Her lips would shut into a thin line, and her eyes fill with tears.

But Grandmother Brown loved babies, and she sang to us all, and rocked us, hours and hours, in that same little chair. All the Pretty Little Horses is a wonderful lullaby. The phrases can be changed, a line or two of hums can be put in at will instead of the words, at will, and the baby drifts off into sleep, floating with the little horses the song blends with the squeak of the rocker and the pat of the foot on the rug. The horrible verse about the "bees and the butterflies" was not sung in our house, and should never be used- -what baby could sleep with such a pitiful and ghastly picture stamped into his dreamy little soul? I still sing it to my girls when they are ill, but they always request that that verse not be sung. And I don't blame them."

All the Pretty Little Horses

A Haitian Lullaby

We employed Francilia, a young peasant girl of the neighborhood, ostensibly as a servant for the three weeks we spent in Carrefour Du Forts [Carrefour Dufort]. Our real reason was not her cleanliness or her ability to cook or her energy in sweeping or her excellence as a laundress, because she had none of these qualities, but because she was a delightful singer. —Alan Lomax, Haiti, 1937

Francilia was not just a tremendous singer—a rèn chante (queen of song)—but a storehouse of traditional song, particularly ceremonial Vodou material. She did, however, record two lullabies for Lomax, “Dododo, sa ki la, se mwen menm la bèl, ouvrè pòt pou mwen” (“Dododo, that's how it is, I'm the beautiful one, hold the door for me”) and “Dodo, dodo, krab nans kalalou* (Sleep, sleep, the crab is in the okra).” The latter is perhaps the best-known berceuse or “cradle song” in Haiti, typically known simply as “Dodo” or in a somewhat different, more localized version as “Dodo titit.”

Unfortunately, Lomax took down precious little biographical information on Francilia—not even her last name. But the warm rapport Alan and his wife Elizabeth had with Francilia is palpable, and her recordings are some of the best fidelity-wise in the entire Haitian collection. That said, when we asked Haitian-American singer, performer, and music therapist Claudia Zanes to record her own arrangement of “Dododo, sa ki la,” none of the seven members of her family she asked could decipher all of the lyrics. So, instead, Claudia recorded her own version of “Dodo,”one that her mother sang to her. “This is a lullaby that many Haitian mamas have sung to their little ones at bedtime,” she told us. “The melody is so sweet and gentle as it lulls one to sleep. It’s a song that brings me back to my childhood.”

*In Haitian kreyol, “kalalou” literally means okra, but it refers to the stew known throughout the Caribbean as callaloo (although the spelling varies). Often this dish is called “Haitian gumbo.”

Dodo, dodo, krab nans kalalou

Dodo

With a lullaby in Kreyol represented here, we investigated a Cajun or Creole performance that we could draw from the extensive recordings the Lomaxes made in 1934 in Southwest Louisiana. Strangely, however, despite the diversity of the material in that collection—including play-party songs, love songs, and ballads sung in domestic settings—nothing could be called a lullaby. Our friend and colleague Dr. Josh Caffery, director of the Center of Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, suggested looking into the short session that John Lomax held at the Lafon Nursing Home in New Orleans in 1937. And indeed, there an elderly woman identified as Ernestine Laban (although this may be LaBowe) sang yet another version of “Dodo,” this one in a surprising mix of Haitian Kreyol and Louisiana Creole.

We had our own trouble deciphering the lyrics; Josh ultimately put us in touch with Dr. Thomas Klingler, Associate Professor of French at Tulane, who kindly provided us with the following translation:

Creole — phonetic spelling

Fe do do mon fiy

Krab dan kalalou

Fe do do mon fiy

Krab dan kalalou.

Papa li (kouri) la rivyèr

Manman li (kouri) (pécher krab)

Fe do do mon fiy

Krabe dan kalalou

Fe do do mon fiy

Krab dan kalalou.

Papa li (kouri) la rivyèr

Manman li (kouri) (pécher krab)

Fe do do mon fiy

Krab dan kalalou

Fe do do mon fiy

Krab dan kalalou.

Creole – Frenchified spelling

Fais do do mon fille

Crabe dans calalou

Fais do do mon fille

Crabe dans calalou.

Papa li (couri) la rivière

Manman li (couri) (pécher crabe)

Fais do do mon fille

Crabe dans calalou

Fais do do mon fille

Crabe dans calalou.

Papa li (couri) la rivière

Manman li (couri) (pécher crabe)

Fais do do mon fille

Crabe dans calalou

Fais do do mon fille

Crabe dans calalou.

English translation

Go to sleep, my daughter

The crab is in the calalou

Go to sleep, my daughter

The crab is in the calalou

Her father went to the river

Her mother went to fish crabs

Go to sleep, my daughter

The crab is in the calalou

Go to sleep, my daughter

The crab is in the calalou

Her father went to the river

Her mother went to fish crabs

Go to sleep, my daughter

The crab is in the calalou

Go to sleep, my daughter

The crab is in the calalou.

*The language is more Haitian Creole than Louisiana Creole, as can be seen mainly in the placement of the possessive determiner after the noun: papa li ‘his/her father,’ manman li ‘his/her mother,’ and, in the Amélie Alexandre version below, papa mwen ‘my father,’ maman mwen ‘my mother.’ However, the possessive determiner is preposed to the noun in mon fiy/ma fiy ‘my daughter/girl,’ so that the language in this version of the song appears to be a mixture of Haitian and Louisiana Creole. —Dr. Klingler

We’d reached out to the fine Québécois traditional singer and arranger Myriam Gendron in the hopes that she might contribute an arrangement of a Francophone Louisiana lullaby through the prism of her own geographic and aesthetic perspectives, but when the one that turned up in the Lafon Nursing Home was preponderantly in Kreyol, Myriam suggested that she provide her own version of the song—which she had also heard as a child!—testifying to just how far-flung the lullaby in fact is. She shared the following, regarding the song specifically and lullabies more generally:

I had a flood in my basement yesterday. When we woke up, boxes of books, pictures and other souvenirs were floating everywhere. I spent the whole day going through my wet memories and deciding whether they were garbage that could be thrown away or flowers that had to be dried under the sun. Not an easy task. Among other things, I came across the baby book my mother made when I was young. She wrote there that I was very sensitive to the lullabies she sang to me. They calmed me instantly.

Nothing surprising: that’s why lullabies exist, right? I’m not sure what it is exactly – their very simple melodic lines, their structural circularity – but they definitely have a soothing effect on us. I like many different types of music, I can listen to very loud and angry stuff, but I think the songs I love the most are the ones that remind me of lullabies. They’re the ones I come back to. It’s the same when I’m writing music. I like to experiment but I always feel the need to return to those simple and soothing structures. They feel like home.

Needless to say, I was very happy when I received the request to participate in this Alan Lomax lullaby project. I think the soothing effect of lullabies is also due to the fact that they come from so far away in time and space. They’re extremely simple on the surface but they have a strong and complicated story embedded in them. They connect us to something we all know and share. It’s primitive and very powerful.

When the curators of the Lomax Archive sent me the field recordings of the French lullabies in the Lomax collection, I recognized bits and pieces of lullabies I’ve known since I was a child. One of them (Fe do do / Krab dan kalalou) was actually not in French but in Haitian Creole. Everyone who grew up in Quebec in the 80’s knows a version of this song because it was sung by the Haitian character Doualé in a very famous kids’ TV show called Passe-Partout. The other one that I knew in another version (Fais dodo Colas mon petit frère) is a very famous French provincial song that we sing to children in Quebec. Most certainly one of the lullabies my mother sang to me when I was a baby.

I think I never realized before I started working on this project that the songs are very similar in structure and lyrics. But now, I’m almost certain they come from the same place. So I decided to reunite them in the shape of a canon. It seemed like the proper way to highlight the multiple layers of time, space and meaning that run through the song.

Oh - I just received a warning on my phone. There’s a tornado watch in Montreal and I have to go pick up the kids. Weather-related disasters are becoming the norm and children are scared. We really need lullabies.

Rocking my Baby to Sleep

This trio of lullabies was recorded during Lomax's 1962 survey of the Eastern Caribbean and Lesser Antilles.

The Big Drum Group version (Carriacou) is the most developed of the three, and touches on the theme of abandonment (a motif we have seen before) as well as the somewhat unexpected cuckolding of the father.

On his visit to Dominica with Antoinette Marchand in 1962, Lomax recorded 75-year old Caroline Telamaque singing what seems to be a variation of the Trinidadian lullaby "Dodo Petit Popo", whose recorded lyrics to its English Creole version are "Dodo petit popo/Mama gone to town/to buy sugar plum/and give popo some". Telamaque had 5 children "alive" (she said she had 14, but only 5 survived) and so many grandchildren and great-grandchild she couldn't count — "about 30 of them"—so one can imagine she sang this tune to many in her life.

Here’s a lullaby that makes no bones about its intentions, expressing a sentiment no doubt many—if not most—parents have felt a desperate need to make plain to their kids: “Little baby, I want you to sleep for me to go do my work.” Although many of us would prefer to skip over the other declaration the singer makes to her audience: “If you’re bad mama won’t love you.” Bruna Bazil sings this and a similar lullaby identified as “Night, Night, Night” in both English and Dominican Creole French.

Ninna Nanna

This is among a session of Sardinian songs recorded by Wanda Sanna, known later (post-1967) as Lady Boothby, when she became the second wife of Tory politician Baron Robert Boothby. Listen to Wanda Sanna introduce the lullaby (in French). She says: "This song — it's a lady wishing that the little girl can fall asleep. It's a song we sing in the middle of Italy, in the area of Macomer and Boze, all those little villages surrounding it. Well, this is a song with a rather … melody, a lullaby that tires the child, and then she falls asleep very quickly."

Cu ti lu dissi

Julia Patinella is a multilingual singer and songwriter currently residing in Brooklyn. After years of immersion as a Flamenco singer in southern Spain, as well as a life-long dedication to the oral traditions of her ancestor’s native Sicily, Julia has developed several original musical projects in Spanish, Italian, Sicilian and English, that draw from her roots, her experience as a first-generation American woman, and urgent socio-political themes. In her performances, she brings forth an expansive repertoire steeped in history and folk traditions, and a richly textured voice that carries the raw emotions of protest, the longing for freedom, and the uncompromising commitment to sing every note with soul.

Due to a miscommunication, we originally approached Julia with the idea of her contributing an arrangement of the ninna nanna above, thinking that she was a Sardinian speaker. Luckily she helped us realize our error, and offered a Sicilian lullaby instead, along with this background:

"Lullabies, especially in Sicilian, my native language, have a very special place in my heart. I discovered something the first time I sang the lullaby that is most dear to me, to a room full of people. The story goes: I spent years in Sevilla, Spain, studying to be a Flamenco singer. I learned some of the most beautiful, complicated and vocally challenging music I had ever heard. I launched my career as a Flamenco singer, and within a few years, I became burnt out from performing vocal acrobatics night after night on little sleep. One morning I woke up while touring in Mexico, and my voice was gone. It went hiding... for months, almost up to a year. Finding myself fighting a crippling sadness every new day that my voice did not return, I needed to find new wings to fly. So, I picked up the guitar for the first time, learned my first three chords, and sang my first song, self-accompanied—a Sicilian lullaby that has been known in our culture for generations called "Cu ti lu dissi." After not performing for months, I nervously took to the stage with a knot in my stomach, and sang this sweet song with shaky guitar skills and a broken raspy voice to a crowd of people for the first time. It seemed there was no one in the room who was not deeply moved by this simple and intuitive folk melody, that appears to transcend culture and language—this short concise repetitive tune known by all in Sicily, that had been used to soothe crying babies by my ancestors for so many generations. Since that day I have found again and again, that no matter where I play or what else I sing, it is that Sicilian lullaby that is every crowd's favorite song."

The songs from this session were recorded in the kitchen of Dolores Fernández Geijo and feature her singing as well as that of her mother, Carolina Geijo, and her aunt, Antonia Geijo, in the village of San Lorenzo near Astorga, in the Maragato region. The Maragatos were known as muleteers on poor and difficult land and for their honesty. Dolores was one of the last great weavers of the area, and in 2001 she recalled that the payments Alan Lomax had had sent from the BBC enabled her, as a young woman with small children, to keep her loom.

Duérmete, niño angelito

In September 1967, Alan Lomax visited Morocco to make field recordings for use in his comparative research on world folk song style. He recorded in Fes, Marrakesh, the Ourika Valley, Ouarzazate, Tinjdad, El Ksiba, Erfoud, and other Berber villages in the High Atlas. One of the only lullabies presented here sung by a male voice, this song was performed by Abdellatif ar-Riffi, an 18-year-old engineering student in Fes, originally from a mixed Arab-Amazigh family from the Rif, near Nador. In the session to which this song belongs, he sings folk hymns and lullabies, both in Moroccan Arabic and in Tarifit, the Amazigh language of the Rif Mountains.

Listen to Abdellatif ar-Riffi translate the Arala Bouyya (in French). . He says, "Oh, Father, bring us some calmness for the baby, to send him calming dreams so that he will go to sleep quickly."

Miriam Elhajli — folk singer, composer-improviser, and musicologist whose work is influenced by the rich musical traditions of her Venezuelan, Moroccan, and North American heritage — agreed to take on not one, but two of the recordings for us. With regard to her own experiences with lullabies, she said:

I wasn't sang many lullabies as a kid, but my grandfather would sing me one he made up - it would go "Te quiere tu mami, Te quiere tu Papi, Te quiere tu Tita, Te quiere tu Tito" just really a song about all the people in my life who love me - at times it would turn humorous and we would add animals or random things.

To prepare for her recording, Miriam reached to a Tarift-speaking Moroccan friend, Atlas Phoenix, who provided an alternative interpretation of the song. He said: "Lalla Buya is a mythical Amazigh personality and she is a woman (A lalla in the Rif dialect is pronounced as Aralla). Her name is Buya. Lalla means M'am or noble lady. She ruled the Northern part of Morocco and Northern part of Algeria; the Greek historian Herodotus mentioned her in his writings."

He also said the young boy singing was not enunciating the vowels so it came off slightly wrong in terms of lyrics, and offered the following:

A lalla buya

A lalla buya

(Oh noble Buya)

A lalla buya awid aghrum (Oh noble Buya, bring us bread!)

A lalla buya awid aman (Oh noble Buya, bring us water!)

A lalla buya aswaddam atay (Oh noble Buya, pour us some tea!)

Alan Lomax considered Texas Gladden one of the three best ballad singers he ever recorded (the others being Almeda Riddle of Arkansas and Scotland’s Jeannie Robertson). He wasn’t alone in admiring her—several folklorists had collected her songs in the 1930s, and, two years after hearing her sing at the White Top Festival in 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt invited Texas and her brother Hobart Smith to perform at the White House. Although her singing had been diminished by ill-health, she recorded a number of shorter pieces for Lomax in 1959—love songs, some ballad verses, and lullabies sung to her granddaughter Cynthia Tuttle, whom Texas addresses here as “Baby Cindy.” Despite her renown, she was never much inclined to travel for the concerts folk revivalists were putting on in the mid-’60s. Besides, when Lomax wondered why she’d never made much “professional use” of her singing, she replied that she’d “been too busy raising babies! When you bring up nine, you have your hands full. All I could sing was lullabies.”

The gifted ballad singer Elizabeth LaPrelle grew up in the musically rich Blue Ridge Mountains of southwestern Virginia, in Wythe County, which borders Texas Gladden’s native Smyth County. Raised in a family of old-time musicians, LaPrelle loved traditional ballads from an early age, and learned about traditional Blue Ridge singing from such masters as Sheila Kay Adams and Ginny Hawker. She recorded this version of "Whole Heap a Little Horses" for her album Rain and Snow back in 2004, and we felt compelled to include it here.

From a selection of Georgian recordings which were copied by Alan Lomax, on the invitation of the Georgian Union of Composers, from the collection at the Georgian Conservatory of Music in Tiflis, Georgia, this lullaby was recorded by Mindiia Zhordaniia at the village of Shilda, district of Qvareli in 1962. "Nana" means lullaby, although the iavnana was also historically sung to sick children. (It’s been suggested that “nana” is derived from the name of a pagan mother goddess.)

A note (presumably Zhordaniia’s) on the tape box reads: "Lullaby – 20 women from Kakheti, region of Shilda. Sung by two choruses singing by turns…. In both choruses there is a soloist backed by the chorus. The second chorus repeats that which was sung by the first chorus. This song is still sung by the people and, according to the belief of the people this song can strengthen sick children."

This version of Señora Santana, a widespread and beloved Mexican lullaby, is one of four recorded by John A. Lomax during his 1939 field trip to Texas, and perhaps the most distinctive. Sung by Olga Acedevo, starts off with the common refrain: "Señora Santana/¿Por qué llora el niño?/Por una manzana/Que se le ha perdido" (Mrs. Santana/Why is the child crying?/Because of an apple/that he has lost) and then diverges into a more traditional lullaby—"Duermete mi niño/duerma se prontito" (Sleep my child/go to sleep soon).

From Ruby T. Lomax's field notes: "Miss Olga Acevedo and Mr. Ruby Wilson were introduced by Professor J.A. Rickard, Professor of History in the College of Arts and Industries, and founder of the Tennessee Folk Lore Society. The singers are students of the college and their recordings were made under the grandstand of the college stadium. Miss Acevedo learned most of her songs from her mother."

Elizabeth Cronin (1879—1956) sang this short but gorgeous Irish dandling song to Alan Lomax in 1951 when he visited her at her home in Ballymakeery, in County Cork. It’s perhaps best known in its “fishy” variant, which many British readers will know, if not from their own childhoods, than from Young’s Seafood commercial that adapted it for their fishmongering purposes. (Or else from composer David Fanshawe’s setting of it that was used as the theme music to the popular BBC 1 series “When the Boat Comes In.) Lomax recorded a verse of the latter as sung by American folk singer, songwriter, and Appalachian dulcimer player Jean Ritchie in 1949, which she learned "not from Mom or Dad or anybody, but from my schoolmates, the little girls and boys, learned it at the creek somewhere." Jean quickly fuses it with “Hush Little Baby.”

The great Scottish Traveler singer Belle Stewart performed these versions of “When the Boat Comes In” in Cant (the Traveler language) and Scots (which she calls English) for the School of Scottish Studies ethnomusicologist Peter Rich Cooke in 1979.

Dance To Your Daddy / Hush Little Baby (Mockingbird Song)

Dance to Your Daddy-O

Singer and multi-instrumentalist Eamon O’Leary was born in Dublin. Following in the footsteps of early Irish recording greats like Michael Coleman, Frank Quinn, and Patsy Touhey, O’Leary settled in New York, now his home of some thirty years. His collaborations are myriad: in addition to long-term partnerships with Jefferson Hamer (as Murphy Beds) and the Alt (his trio with Nuala Kennedy and John Doyle), he’s worked with Sam Amidon, Beth Orton, Bonnie Prince Billy, Anais Mitchell, Anna and Elizabeth, and Martin Hayes (The Gloaming). He and Canadian soprano Janelle Lucyk contributed a version of the far-flung lullaby “Dance to Your Daddy,” on which Eamon shared the following reflection:

I couldn't say for certain where I first heard it but it's a song that seems to have always stayed with me—that (like the best folk songs) has taken up residence and moved through the world with me. In that time it has changed shape and significance in my life but has always endured. Although I'm in the habit of performing folk songs on stage for a living, this is one that has occupied a more intimate or personal part of my life. When I myself became daddy to a little laddie this was instinctively the song that I came back to time and again—whether in playful or perhaps consoling mood. Sometimes one of the versions swimming around in my head seemed appropriate, sometimes another...

Dance to your Daddy my little laddie

Dance to your Daddy my little man

You will have a fishy in your little dishy

You will have a fishy when the boat comes in

That light and lilting version was suited to many occasions but at times I'd reach for the more solemn sounding minor key setting that I first heard from Andy Irvine and Sweeney's Men...

When thou art a man and fit to take a wife

Thou shalt wed a maid and love her all your life

She shall be your lassie thou shalt be her her man

Dance to your Daddy, my little man

Strangely moving now to recall those days and nights and those lines softly intoned to a cradled infant—when for brief moments all the generations past, present and future seemed to join us in song.

Hush, the Waves are Rolling In

Although identified in late nineteenth-century texts as “An Old Gaelic Lullaby” and “An Old Gaelic Cradle-Song,” we’ve not succeeded in locating any such Gaelic original of this song. And while the use of “knowes” certainly argues for Scots origins, we’ve been unable to find any versions published in Scottish sources. It turns up in well over a dozen books of children’s verse between 1870 and the 1920s, as well as in a sheet-music arrangement by pioneering musicologist Mildred Hill (of “Happy Birthday” fame).

Joan Shelley is a songwriter and singer living in Louisville, Kentucky. She draws inspiration from traditional and traditionally-minded performers from her native state, as well as those from the British Isles, but she’s not a folksinger. Her disposition aligns more closely with that of, say, Roger Miller, Dolly Parton, or her fellow Kentuckian Tom T. Hall, who once explained—simply, succinctly, in a song—I Witness Life.

She’s also not so much a confessional songwriter, singing less of her life and more of her place: of landscapes and watercourses; of flora and fauna; of seasons changing and years departing and the ineluctable attempt of humans to make some small sense of all—or, at best, some—of it. Her perspective and performances both have been described, apparently positively, as “pure,” but there’s no trace of the Pollyanna and there’s little of the pastoral, either: her work instead wrestles with the possibility of reconciling, if only for a moment, the perceived “natural” world with its reflection—sometimes, relatively speaking, clear; other times hopelessly distorted—in the human heart, mind, and footprint.

Joan’s rendering of “Hush, the Waves” was adapted from the singing of 14-year-old Clarice Garland, recorded in Pineville, in Bell County, Kentucky, by Mary Elizabeth Barnicle in 1938. Joan shared this reflection with us:

Somewhere I learned of a rule—I want to say it was from Beethoven—that the way to capture an audience is to write a melody that a listener can start to feel they can predict, and then to interrupt it. Even the simplest melodies can capture attention and cause delight when done this way. Form can mesmerize.

Before I became a mother I thought a great lullaby was one whose vowels and consonants and rhymes would find their perfect balance and hypnotize a child to sleep. But once I was a mother, I realized there was no magic song that could do this. Not on its own. During those hours in the dark, trying to hold this suddenly hungry, then suddenly wide awake and needy infant, I realized that the songs were mostly for me. My child needed me to be there, awake when she was, and calm enough to nurse her. So I needed songs that would soothe me. While her growing body dictated when she slept and woke, the songs were there for my captive mind. The songs were there for my wracked nervous system: unable to use my hands or my body for my own purposes, my own needs, they brought me into the present moment as much as possible for this new being. I could give her something beautiful—a melody she could follow—while giving myself the poem, feeling, or story that the song conveyed. A sense of the connection to all the people who have sung the song before me.

Now I think the task of the melody is to mesmerize the child and the task of the lyrics is to soothe the singer.

When I heard “Hush the Waves” sung by Clarice Garland, I was immediately drawn in by the simple melody, the way it plucks up and down the scale, then takes these upward leaps—“on they come”—and ends in the delicate little box step that is the refrain, “ba-by sleeps at home.” The story lets you follow the humans and their animals amid a storm. Then the mysterious word “knowes” captures my curiosity: Scottish, then. So who brought this song? How did it get to Kentucky? How many people have sung it to their child… that is the joy of an archive like this. This is a story that I could think about from different angles endlessly.

Before my daughter was born, a friend of mine had cross-stitched these words. We had them framed and put up on the wall in front of the rocking chair. In the most difficult sleepless hours I would read them because I needed them. They said:

Stay calm

Breathe deeply

You are loved.

Songs, even the darker and sadder ones, have ways of stitching these elements together: the breath, the presence, the love (however close or far away, however forlorn). The good lullabies do this. One aspect of their power is that they are shared among people over time. I want my daughter to know great songs, and I want her friends to know them too. I cannot look into their futures, but we all see the uncertainty there for them. I want to stitch this up on the wall: Your life may be a series of predictable steps until it is not. When those interruptions come, I hope you have in yourself the songs that will anchor you to the present and help you find the beauty there.